After the War

Peter Billam

|

This article was written in 2013 for the old paper Music Forum magazine; it was then re-published in the on-line Music Forum magazine, which is no longer available. It was presented as a lecture to the Musicological Society of Australia in Hobart; check out a recording 20140813_after_the_war.mp3 and the associated handout. It owes much to its sources, which should be consulted for details of the original references. |

I was born in 1948, just after the war, so the musical culture I inherited was from the generation before the war.

That had been an extraordinarily brilliant time. For example, just the couple of years around 1910 gave us Stravinsky's Petrushka, and the Rite of Spring, Bartók's Bluebeard's Castle, Debussy's La Mer and Jeux, Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe, Schoenberg's Five Orchestral Pieces, Busoni's Doktor Faust, Delius' A Mass of Life, Scriabin's Prometheus, Holst's The Planets, all the late Mahler symphonies including The Song Of The Earth, and Elektra and Salome from Richard Strauss. And those are just the big pieces. All that in just a couple of years! It's a phenomenal outpouring.

I grew up listening to that, and sort of expecting to live in a world in which that kind of cultural flowering would be the norm.

I remember, when I would have been about nine, having just learned that the population of the world was about ten times greater than in Beethoven's day, I asked my mother, "Where are the ten Beethovens then?"

Of course, she didn't know the answer.

Then, when I grew up in the late sixties and got to know the composing scene in London, all was post-Webern serialism, Darmstadt, Tanglewood, Universal Edition and associated competitions, festivals and journals. Schoenberg, Berg and especially Webern were idols, and Metre, Harmony, Melody and Theme were deprecated. The old German music publishers, like Schott and Peters and Bote und Bock, continued selling their Schubert and Brahms and so on, but did not add to their catalogues. Universal Edition published works by hundreds of young composers, who, producing either post-Webern serialist, or aleatoric, or graphically notated, or conceptual works, tried as hard as they could to produce important music; but because of the genre it was being written in the public didn't take to it, and neither did most performers.

It was clear to me that a cultural tradition that had been alive before the war was there no longer. What had happened ?

Before 1944, there was the OWI (Office of War Information) which, in spite of its name, was a civilian organisation reporting to the State Department. The OWI 's job was to run cultural affairs in Allied-occupied countries: theatre, literature, concerts, magazines, radio, newspapers and so on. Most of their staff were idealistic, cultured young east-coast graduates; composers Roy Harris and Marc Blitzstein headed their Music Division and the ABSIE (American Broadcasting Station in Europe).

In 1944, with the invasion of France looming, Eisenhower changed the OWI into the PWD (Psychological Warfare Division), giving it greater autonomy from the civilian agencies, and more military associations.

Then, within occupied Germany, a military government was formed, and in August 1945 the PWD, and most of its staff, were taken over by the ICD (Information Control Division), reporting to OMGUS (Office of Military Government United States), under the command of General Robert McClure. He had authority over 37 newspapers, 6 radio stations, 314 theatres, 642 cinemas and 237 book-publishers.

McClure argued that ICD's mission was to make the individual German aware that "we have waged war against Germany, and not only against the Nazis" and "of his personal share in the collective German responsibility for the acts of the Nazis and militarists", and to "accept Germany's guilt as a nation as his personal guilt".

So he set about stripping away "German misconceptions about Germany and its relationship with the world", of which one of the most important was the Germans' pride in their musical tradition. Nazi propaganda had promoted German Music proudly: the prominence of German composers had been promoted as evidence of Aryan superiority, and the Nuremburg rallies were choreographed to the music of Beethoven, Bruckner and Wagner. The Nazis ran a big advertising campaign "Pflegt Deutsche Hausmusik!", ("Play German Chamber Music in Your Home!"), so obviously General McClure wasn't keen to encourage the playing of German Chamber Music.

Furtwängler was blacklisted for two years, not because the Americans were blunderers or cultural illiterates, but because ICD saw the conductor as he saw himself: as a preeminent symbol of German musical culture. But whereas Furtwängler cherished that culture as the wellspring of civilisation, the ICD considered it the birthplace of Nazism.

However, while Robert McClure and the upper levels of the hierarchy wanted an ongoing mopping-up operation against German culture, he was undermined by his own staff in the ICD Music Branch, who felt their job was to restart German culture, so as not to allow the Nazis and Soviets to look like goodies and the Americans like baddies.

The fates of German musicians were determined, largely at random, by this bureaucratic civil war, whose outcomes were made even more random by regional committees controling arts in the Laender, and by interaction with decisions made in the British, French and Russian zones. This process decided the concert performances of composers like Egk, Hindemith, Orff, Pfitzner, and Strauss, and the careers of Patzak, Schwarzkopf, Rosbaud, Munch, Leitner, Krauss, Knappertsbusch, Griendl, Gieseking, Tietjen, Jochum, Solti, Böhm, Leinsdorf, Karajan, Furtwängler and their whole generation.

Meanwhile, the broader Denazification of german society was under way; all germans were required to fill in a form, a Fragebogen, detailing how close they were to the Nazi party. These forms were compared with each other, and with Nazi-party records, and anyone who was a party-member or a close associate, found themselves permanently unemployed in the post-war era. The ICD was soon overwhelmed by the scale of that task, but Michael Josselson and Nicholas Nabokov (the cousin of Vladimir the famous novelist), who ended up running the Congress for Cultural Freedom, cut their teeth working in the OMGUS offices comparing those forms, and making denazification recommendations accordingly.

American music, in the eyes of senior planning officials, was always thought to have a special role to play in Germany. Especially, the State Department authorities saw American culture as the vanguard of democratisation, and refused to authorise music by non-Americans, or even of émigrés such as Hindemith, Martinu or Krenek; these composers were not deemed sufficiently representative of America to have reeducational value. So the Music Branch promoted works by Piston, Harris, Schuman, Thompson, Copland, Barber, and Gershwin. Robert McBride's Strawberry Jam Overture went down very badly, Piston's Incredible Flutist and Concertino for Piano and Orchestra also went badly. Several composers working for the Music Branch took the opportunity to get their own works performed, like John Bitter, John Evarts, Harrison Kerr, Everett Helm, and also those works did not convince German audiences that American music had any value. But Menotti's The Old Maid and the Thief went OK, and Barber's Adagio was well received. The real hit was Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, which however was double-edged, because it does portray life in America as harsh and uncivilised, and unforgiving especially for blacks.

Although ICD's Music Branch tried to get musical culture restarted, they only really had influence over performance. They had little say in the future of the composing tradition itself. And what happened to the composing tradition? By 1946 already, while germans were still starving, and freezing in winter, OMGUS had already set up the Darmstadt Music School.

OMGUS knew right from the beginning that Darmstadt music was unloved. I quote an official OMGUS report from 1947: "It was generally conceded that much of this music was worthless and had better been left unplayed. The over-emphasis on twelve-tone music was regretted. One critic described the concerts as 'The Triumph of Dillettantism' . . . The French students remained aloof from the others and acted in a snobbish way, and their teacher, Leibowitz, represents and admits as valid only the most radical kind of music and is openly disdainful of any other. His attitude is aped by his students. It was generally felt that next year's course must follow a different, more catholic, pattern." But that change did not occur.

In August 1947, the Music Branch had managed to get Furtwängler cleared, and permitted to conduct a benefit concert for jewish refugees, with the American violinist Yehudi Menuhin as soloist. But others in the hierarchy were not in favour. The Military Police checked the papers of everyone coming in to the hall; they relented when the concert was already an hour late in starting, but throughout the performance they moved up and down the aisles, checking all passes and evicting anyone whose papers were not in order. They also cleared the hall at the end of the music, before anyone could applaud.

But meanwhile, the American enemy was changing from Germany to Russia.

Addressing Congress in March 1947 on the situation in Greece, where a Communist takeover threatened, President Truman appealed in apocalyptic language for a new age of American intervention: "at the present moment in world history nearly every nation must choose between alternative ways of life!" he declared. This ideological call-to-arms was immediately enshrined as the Truman Doctrine.

On 5 June 1947, General George Marshall, the US Army's wartime Chief of Staff and now Truman's Secretary of State, announced the Marshall Plan to deal with the 'great crisis'. Warning that "the whole world [and] . . . the way of life we have known is literally in the balance", he called upon the New World to step into the breach with a crash programme of financial credits and large-scale material assistance, and thus prevent the collapse of the Old World.

On 26 July, the National Security Act created the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency), to coordinate military and diplomatic intelligence, and to carry out unspecified "services of common concern" and "such other functions and duties" as the National Security Council might direct. Its covert operations wing was called the OPC (Office of Policy Coordination) and was made part of the Policy Planning Staff in the State Department.

Meanwhile on the other side, in October 1947, ComInform (the Communist Information Bureau) held its first meeting in Belgrade. Formed in Moscow the previous September, ComInform replaced the defunct ComIntern. Andrei Zhadanov, architect of Stalin's ruthless cultural policy, told the Communists of western Europe that they had: "achieved considerable success in conduction work among the Intelligentsia. Proof of this is the fact that in these countries the best people of science, art and literature belong to the Communist Party, are heading the movement of the progressive struggle, are winning more and more intellectuals to the cause of Communism."

In March 1949 ComInform boldly staged a "Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace" in the New York Waldorf Astoria, where it was besieged by right-wing protesters. Nicolas Nabokov attended a panel where Shostakovich was one of the speakers. After a dull session, Nabokov was finally given the floor. "On such-and-such a date in Pravda appeared an unsigned article that had all the looks of an editorial. It concerned three western composers: Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schoenberg, and Igor Stravinsky. In this article, they were branded, all three of them, as 'obscurantists', 'decadent bourgeois formalists' and 'lackeys of imperialist capitalism'. The performance of their music should 'therefore be prohibited in the U.S.S.R.' Does Mr Shostakovich personally agree with this official view as printed in Pravda?". "Provokatsya! (Provocation!)" cried the Russians, as Shostakovich received whispered instructions from his KGB 'nurse'. The composer then stood up, was handed a microphone and, ashen face turned down to the floorboards, murmured in Russian, "I fully agree with this official view as printed in Pravda." Rumours that Shostakovich had been ordered to attend the conference by Stalin himself had reached this New York gathering; any display of independent spirit on his part was a life or death matter. Nabokov was throwing punches at a man whose arms were tied behind his back.

The Waldorf Astoria conference was a humiliation for its Communist backers. "It was," said one observer, "a propagandist's nightmare, a fiasco that proved the last hurrah for the idea that the ideological interests of Stalinist Russia could be grafted onto progressive traditions in America." The American Communist Party was now in retreat, its membership at an all-time low, its prestige irrevocably tarnished. Just when claims of a Communist conspiracy began to take a feverish grip, Stalin's strategists all but turned their back on America, and concentrated instead on extending influence in Europe.

The American reply was a large congess in Berlin in April 1950, called the Congress for Cultural Freedom, which is a story in itself, but it went a lot better than the Waldorf Astoria. The OPC then made the Congress for Cultural Freedom a permanent institution, gave it the codename QKOPERA, appointed Nabokov and Josselson to run it, and moved its headquarters to the relative security of Paris.

OMGUS was rapidly down-sized and starved of funds, and by 1950 it had been dissolved. But Darmstadt remained. The idol of Darmstadt was Webern, who certainly wasn't chosen for being anti-Nazi; he had written an extatic, almost orgasmic, letter rejoicing in Hitler's rise to power. That letter is quoted in Alex Ross' book: The Rest Is Noise.

Both the Nazis and the Russians had run fierce propaganda campaigns - posters, newspaper cartoons and so on - attacking Americans as people with no culture, only interested in money and weapons. So the Congress started a huge campaign to show that Americans could do culture just as well as Europeans, and that Art under Capitalism has a creative fervour that is suppressed under Nazism or Communism.

In cinema, Hollywood produced films like An American in Paris (1951), featuring Gershwin's music, and portraying Americans as young, vigorous and scrupulously honourable people, who loved Europe, and who loved culture and did it superbly: just as well as Europeans, but newer.

On 1 April 1952, the Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century festival opened in Paris with The Rite of Spring performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Pierre Monteux, who had premiered it thirty-nine years earlier. It was a glittering event, with Stravinsky in attendance, flanked by the French President and his wife. For thirty days, the Congress for Cultural Freedom showered Paris with a hundred symphonies, concertos, operas and ballets by over seventy twentieth-century composers. There were nine orchestras, including the Vienna Philharmonic, the RIAS, the Suisse Romande, the Santa Cecilia, the National Radiodiffusion Française. Topping the bill were those composers who had been banned by Hitler or Stalin or, preferably, by both. There were works by Arnold Schoenberg, driven out of Germany as a Jew and a composer of 'decadent music' in 1933, and denounced as "anti-aesthetic, anti-harmonic, chaotic and inane" by Russian music 'critics'; by Paul Hindemith, another refugee from Nazi Germany, derided by Stalinists for initiating a whole school of "graphic linear pseudo-counterpoint which is slavishly followed by so many pseudo-modernists in Europe and America"; and Claude Debussy, under whose 'Impressionist tree' the 'fleurs du mal of modernism' had been allowed to grow, according to Sovietskaya Muzyka.

Also representing the "validity of the creative effort of our century" were works by Barber, Walton, Mahler, Satie, Bartók, Villa-Lobos, Pizzetti, Rieti, Malipiero, Georges Auric (listed with Darius Milhaud in Sovietskaya Muzyka as "servile teasers of the snobbish bourgeois tastes of a capitalist city"), Honneger, Jean Françaix, Sauget, Poulenc and Aaron Copland (who was grouped with psychiatrists Freud and Borneigg, philosopher Bergson, and 'gangsters' Raymond Mortimer and Bertrand Russell, as false authorities to whom Soviet musicologists and critics should never refer). Stravinsky conducted his own Oedipus Rex, for which Jean Cocteau designed the set and the choreography.

Even British intelligence was aghast at the scale on which its American counterpart was endowing the cultural Cold War; Malcolm Muggeridge later wrote: "How soon our British setup was overtaken in personnel, zest and scale of operation, above all, in expendable cash! The OSS-CIA network, with ramifications all over the world, came to outclass our once legendary Secret Service as a sleek Cadillac does an ancient hansom cab."

In cinema, Hollywood produced Roman Holiday (1953).

The next festival Nabokov arranged was his answer to Herbert Read's criticism of the retrospective nature of the Paris venture: "Let our next exhibition be, then, not a complacent look at the past, but a confident look into the future !" At a press conference in New York in February 1953, Nabokov announced: "With that festival we shut the door of the past," he said. "We said, in effect, here are the great works. They are no longer 'modern' even though they originated in the twentieth century. They are now a part of history. Now, I have a new plan . . . we are going to have a composer's contest that is unlike any other competition ever held."

The International Conference of Twentieth Century Music, to be held in Rome in April 1954, announced the Congress' commitment to the promotion of avant-garde composition. It was to place the Congress firmly on the map as part of the vanguard in musical experiment, and offered the world a rich example of the kind of music expressly forbidden by Stalin.

Money poured in from the Farfield Foundation, to endow the competition with prizes totalling 25,000 Swiss francs for the best violin concerto, short symphony, and chamber music for voice and instruments. The press release announced that the festival, "designed to prove that art thrives on freedom", was the beneficiary of a generous donation from "U.S. gin and yeast heir Julius Fleischmann", who was also brought in to negotiate with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, which agreed to perform the winning composition at its subsiduary, Tanglewood (by 1953, eight of the eleven members of the music advisory board of the Congress were associated with the Tanglewood music school). Nabokov sent the first invitation to his old friend, Igor Stravinsky, paying expenses of $5,000 for the maestro, wife and secretary to attend. Stravinsky also chaired the music advisory board for the festival, alongside Samuel Barber, Boris Blacher, Benjamin Britten, Carlos Chavez, Luigi Dallapiccola, Arthur Honegger, Francesco Malipiero, Frank Martin, Darius Milhaud and Virgil Thompson. Charles Munch had proposed that Toscanini be invited to join the board, but Nabokov refused: "the name of Toscanini connected with a project concerning contemporary music sounds, to say the least, anachronistic. The good Maestro . . . has been a consistent and determined enemy of contemporary music, and has at many occasions attacked its main protagonists."

In early 1954, the Congress set up a festival office in the noble surroundings of the Palazzo Pecci, courtesy of Count Pecci-Blunt, a close friend of Nabokov's, and, despite his title, an American citizen. Treasurer Pierre Bolomey organised a credit line with the Congress's Chase National Bank account in Basle, through which CIA money was funnelled. Pecci-Blunt made a personal contribution of $1300, and a further $10,000 was channelled through Denis de Rougemont's Centre Européen de la Culture, which was also receiving money from the Farfield Foundation, and was given top billing on the programme. Arrangements were secured for the travel of Leontyne Price, and round trip tickets dispatched to Aaron Copland, Michael Tippett, Joseph Fuchs and Ben Weber.

In March 1954, Nabokov announced the festival line-up. With a heavy concentration on atonal, dodecaphonic composition, the aesthetic direction of the event pointed very much to the progressive avant-garde of Alban Berg, Elliot Carter, Luigi Dallapiccola and Luigi Nono. Amongst the 'new' composers were Peter Racine Fricker, Lou Harrison and Mario Peragallo, all of whose work was influenced in varying degrees by twelve-tone composition. They were, on the whole, well received. Musical America noted that "most of the composers and critics making up the committees responsible for the concerts have not been known in the past for their friendliness to dodecaphonic principles or proponents. For this reason, the programs they offered were not only surprising, but encouraging as well." A recent convert to twelve-tone music was Stravinsky, whose presence in Rome signalled a major moment in the convergence of modernist tributaries in the serialist 'orthodoxy'. For Nabokov, there was a clear political message in promoting music which did away with old hierarchies, as a liberation from outdated laws about music's inner logic. Later, critics would wonder whether serialism had broken its emancipatory promise, driving music into a modernist cul-de-sac where it sat, restricted and difficult, tyrranised by despotic formulae, and commanding an increasingly specialised audience. Susan Sontag wrote: "Towards its squawks and thumps, we were deferential - we knew we were supposed to appreciate ugly music; we listened devoutly to the Toch, the Krenek, the Hindemith, the Webern, the Schoenberg, whatever (we had enormous appetites and strong stomachs)." Even the most deferential amongst those attending the Congress festival in Rome whistled and shouted when one performance turned into a 'private soliloquy', and when Hans Werner Henze's twelve-tone opera Boulevard Solitude was premiered, the audience could be forgiven for feeling as if it was travelling along a via dolorosa.

Perhaps sensing a challenge to his own brand of difficulty, Pierre Boulez wrote Nabokov a furious letter larded with insults. Nabokov, he said, was encouraging a "folklore of mediocrity", nurtured by petty bureaucrats obsessed with the number twelve - "A Council of Twelve, a Committee of Twelve, a Jury of Twelve" - but who understood nothing of the creative process. Boulez went on to accuse the Congress of manipulating young composers by offering them large prizes (the winners were Lou Harrison, Giselher Klebe, Jean-Louis Martinet, Mario Peragallo, and Vladimir Vogel).

In 1955 I was seven years old in London; LPs arrived and Saga Records appeared, costing just ten shillings - about 70 cents - and featuring only American or British artists. I grew up listening to those LPs, to Maurice Cole playing the Well-Tempered Clavier, and the Fine Arts Quartet playing Beethoven opus 131 and the six Bartók quartets.

I didn't yet realise it, but by 1955, all the machinery was in place that I would get to know when making music in London in the late sixties: Darmstadt, Tanglewood, Universal Edition, the competitions and festivals and journals, and underlying all, post-Webern serialism.

The Congress for Cultural Freedom was dissolved in 1967, after years of leaks about its funding; by then, the CIA funding had become such public knowledge that most of the governing committee resigned in a rush pretending they hadn't been told, and the Congress was dissolved. But Universal Edition and post-Webern serialism were already in place, and they lived on.

Composing is half the division-of-labour which defines the western art-music culture, and no body can survive for long with its head severed. Between them, OMGUS and the Congress for Cultural Freedom severed the composing tradition of classical music, and preserved classical music as a teaching and performing tradition with a static repertoire, knowing that, in the recording era, a static repertoire can not survive.

The most important source books are:

- on OMGUS: Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification and the Americans, 1945 to 1953, by David Monod

- on the Congress for Cultural Freedom: Who Paid the Piper by Frances Stonor Saunders

- The Rest is Noise by Alex Ross

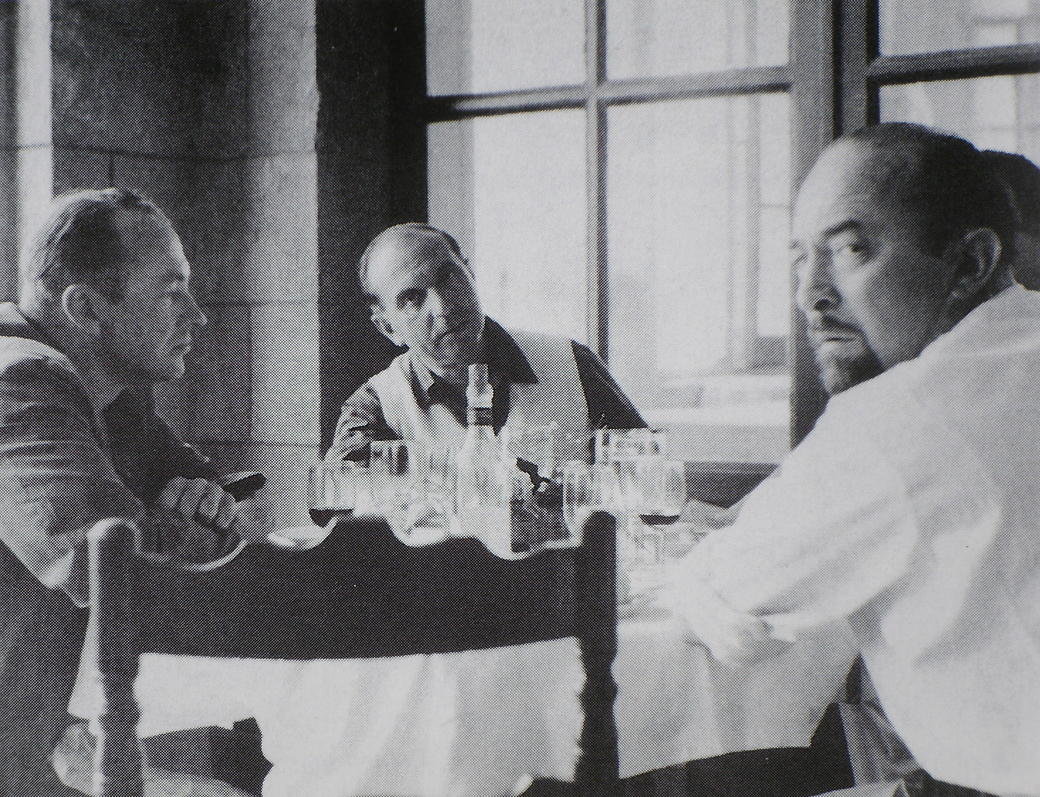

Left to right:

Tom Braden,

the CIA agent who put together the

International Organisations Division,

which ran dozens of fronts including the

Congress for Cultural Freedom

The Congress for Cultural Freedom 'apparat' at a working lunch

near Geneva: John Hunt,

Michael Josselson

and

Melvin Lasky

Michael Josselson,

Nicolas Nabokov

and his wife Marie-Claire,

at the Vienna Opera House in 1957.