Die Deutung der Skizzen Beethovens zur Erkenntnis seines Stils

Paul Mies, 1925

Part 1. The melodic line

Translated by Doris L. Mackinnon as

Beethoven's Sketches:

an analysis of his style based on a study of his sketch-book

publ. Oxford University Press 1929, reprinted Dover 1974

1. The melodic line:

(a) Up-beat and 'curtain'

- 5

(b) The melodic apex and its treatment

- 16

(c) Repetition of notes

- 35

(d) Suspension: absolute melodic structure

- 39

II. The melodic form:

(a) The types of melody

- 44

(b) Threefold repetition

- 46

(c) Avoidance of sequences and uniform rhythms;

characteristic relations between the melodic types, and their changes

- 56

(d) Sequence-contractions

- 76

(e) Transformation of the types

- 85

(f) Themes with irregular number of bars

- 101

(g) Melodic breadth and elimination of caesurae

- 102

(h) The fugue theme

- 110

Index of Opus-numbers

List of Abbreviations

Bibliography

Editor's notes

INTRODUCTION

' . . . To write the history of Beethoven's inner and

outer life would be a wonderful undertaking.'

Thus Schumann wrote in the year 1838

(Briefe, Neue Folge, II. Aufl., p.122).

And perhaps no other musician offers conditions so favourable for

the study of his inner history (i.e. the growth of the

musical ideas, motives, themes and completed works).

Writers have been quick to see this.

Special mention must be made of G. Nottebohm, who, in a large number

of works, opened Beethoven's sketch-books to us and

therewith the composer's inner history - a most laborious

task, in view of the almost illegible nature of

much of the manuscript. Schumann's idea,

that genius must be aided by a will of iron

(Gesammelte Schriften, P. Reclam, vol. iii, p.126),

might have been expressed with special reference to these sketch-books.

For, through them, it is often possible to trace, step by step, how the

most sublime melodies take origin in something very simple.

It is often said that Beethoven's 'daemoniacal constructive power'

(H. Schenker, Erläuterungsausgabe zur Sonate Op.111, p.64)

always succeeded in getting the best end-result from what he had sketched.

'And though these sketches not infrequently give an impression of

hesitation and groping, our admiration revives at sight of this power

of self-criticism, brought to the pitch of genius;

and we marvel at the way in which, after everything has been tested,

it confidently retains that which is best.

I have had the opportunity of examining not a few of Beethoven's

sketch-books; but I have never come across an instance where I was not

bound to admit that what he selected was really the most beautiful'

(O. Jahn, Gerammelte Aufsätze über Musik, p.244).

'One cannot but be struck by the

way in which Beethoven's admirable artistic instinct

infallibly selects from out a mass of sketches the best

reading.' (M. Friedländer,

Jahrbuch der Musikbibliotek Peters, 14. Jahrg. p.19)

And Nottebohm (N. II, p.iX) lays stress on the

importance of these sketches for 'the history of his

evolution as an artist'. ln his first publication (N. 65, p.7)

he says: 'Once it is shown that Beethoven never

moved in a rut (and how else would anyone describe his

independence of any conventional method of procedure ?)

it is obvious that we shall not discover from the

sketch-books what was the inner law that guided him

in his creative work.' By this Nottebohm meant that

Beethoven sometimes sketched out a large plan as the

commencement, and sometimes began with the detail.

And clearly he was thinking of the same thing when

later (N. II, p.lx) he wrote: 'What one sees in Beethoven's

sketch-books occurs over and over again: and

it would be so much waste effort to repeat the same

remark or explanation with regard to each of the sketches,

thrown out, as they are, now in one direction and now in another.'

More recent investigators, whose endeavour has been to penetrate so

far as possible the idiosyncrasies of Beethoven's musical style,

have taken up one instance or another from the sketch-books,

and from these have drawn important conclusions as regards

the final form and the other works. Gal (pp.60, 72),

for instance, through a comparison of this kind, has

revealed the infrequency of suspensions and of chromaticism

in Beethoven's music, the result of which is

an idiosyncrasy of the melody to which he gives the

name 'absolute'.

Becking

(pp.128, 137, 140) has

shown what the special features of Beethoven's scherzo

theme are, and with what sureness these were developed

from sketches that at first were framed quite differently.

Such examples, however, deal with isolated instances

from the sketch-books, and not with a comparison drawn

from the wealth of material which these contain.

Again and again

(P. Mies, Stilmomente und Ausdrucksstilformen in Brahmsschen Lied, p.3)

I have insisted that, while a single

instance may be of great interest, yet, for determining

points of style, it is of immense value to collect together

a number of such instances and make a comparison

between them. If one carefully goes through the sketch-books

published by Nottebohm, one sees that actually

a number of groups can be formed, in which similar

alterations were made on the original drafts: as, for

instance, where melodies lacking an up-beat were given one,

or where melodies of a certain form were re-shaped

although the main motive was retained; and so forth.

We are justified in concluding that to Beethoven the

final reading represented an advance on the sketches,

and that it is in the final selection that the individual

features of his style will therefore be most fully expressed.

The direction of the alteration draws our

attention to the points that Beethoven's musical sense

selected as the best. The laws governing his art are thus revealed;

these are the style determinants that must be grasped.

In a special section (II) we shall consider

to what extent the alterations were made with deliberate intent,

and to what extent they were unconscious.

In addition to noting the similarity of the changes that he made,

it is well worth while to observe what Beethoven chose to retain.

For these must also be things that he thought good and valuable

and in correspondence with his ideas as an artist:

by studying them we may get further clue to his musical idiosyncrasy.

The following study is based on this line of argument.

The main material is taken from the four works [2]

published by Nottebohm, I have also, of course, drawn

on other sources, such as Schenker's editions, Thayer's

biography, etc. It is obvious, and indeed inevitable,

that a number of the conclusions I submit here must

coincide with those of other investigators who have

interested themselves in Beethoven's style

(Gal, Fischer, Jalowetz, Becking):

the researches of these authors,

since they are based on the completed work,

must necessarily include these points of style, which, in the

present work, are indicated by the alterations and retentions.

The use of Nottebohm's works instead of the

original sketch-books imposes a certain restriction;

for while Nottebohm noted the essential points concerning

the themes and the alterations made in these,

it was only in the sketch-book devoted to the Eroica (N. 80)

that he enlarged on the changes in the working-out, etc.

In this essay, style idiosyncrasies are determined

according as Beethoven altered or retained his initial idea.

This limitation is necessary: there is the difficulty

in interpreting the sketch-books; and, still more

important, the fact that, even where one can do so,

a general view of the manifold phenomena they reveal is not easy.

Now, for such a study as I propose, this wide

and continuous survey is just what is necessary.

I believe, however, that, by the method I have adopted,

I have succeeded in tracing to their objective foundations

the essential peculiarities of Beethoven's melodic structure.

PART 1. STYLE DETERMINANTS

I THE MELODIC LINE

(a) Up-beat and 'curtain'.

FISCHER (p.50) has emphasized the importance in the

Viennese classical style of the lively up-beat, combined

with sustained endings to the motives. As a matter

of fact, in the sketch-books there are a large number

of instances in which melodies, originally without up-beat,

are given one later on. It is at once obvious that

Beethoven attached importance to up-beats of this kind;

otherwise he would not have changed the original ideas.

The reasons for inserting an up-beat are several.

Frequently all that had to be done was to impart greater

movement and tension to an existing up-beat.

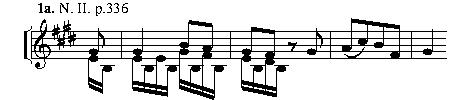

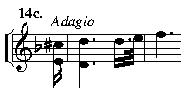

There is an example of this in the piano sonata Op.90:

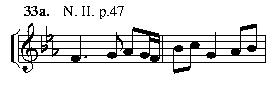

It is also to be noted here that at first the melodic line

began with the repetition of a note. Later on I shall

show in more detail that Beethoven preferred to avoid

such repetitions. So the up-beat G sharp was changed

to E, F sharp.

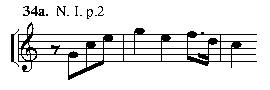

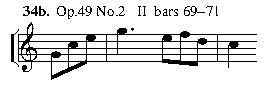

The same thing is shown by the change

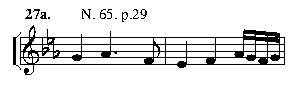

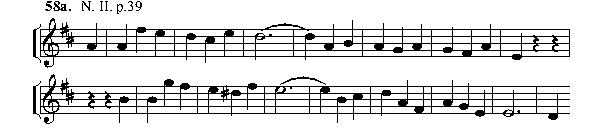

in the up-beat in No. 2 of the song-cycle Op.98:

Here the harmonisation shows something further;

to the key of G its dominant D has been prefixed.

This makes the up-beat more tense, and forces it

towards the principal key.

Sonata Op.22 also shows a

deliberate emphasising of the dominant in the up-beat.

Moreover, by this device Beethoven avoids having the

first note of the melody as apex: I shall return to this point

later.

Often this tension in the dominant is evidently

Beethoven's reason for introducing an up-beat in a

tune that previously lacked it.

(Eisner speaks of the 'impetus' of Beethoven's up-beats.)

One of the most striking

examples is the trio in the minuet of the eighth

symphony. Ex.4 gives the process of evolution; only

in the final form does the up-beat C, D, E occur, whereby

the dominant C major obviously imparts tension to the beginning.

(Concerning the reading of this bar see Müller-Reuter, Lexikon

der deutschen Kunstliteratur, Nachtrag zu Bd.I, p.31.)

Much of the same requirement has produced the up-beat

in the theme of the Cello sonata Op.102. I.

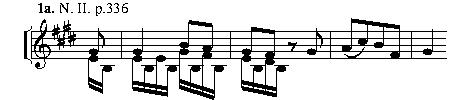

The adagio in the quartet in E flat major, Op.127,

shows the same sort of thing. The theme in A flat

major, originally without up-beat, is given one by the

notes in which again the dominant prevails.

At the same time, the melody receives two

introductory bars on the dominant seventh - a 'curtain',

to use Riemann's terminology.

(System der musikalischen Rhytmik und Metrik, p.230.)

And these brief 'curtains', which appear, especially

in the later works, in melodies originally without up-beat,

must have seemed to Beethoven of great importance:

in the Sketches they often do not occur at all.

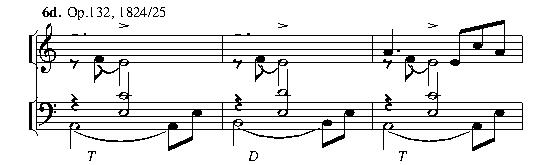

I would instance the theme of the allegro appassionato in the

A minor quartet, Op, 132. Beethoven often began

thus: he even thought of using it for the finale of the

ninth symphony. Ex.6 brings together some sketches,

the second of which has an up-beat, and the final version

a two-bar curtain over tonic and dominant.

The eight-bar introduction to the scherzo of the ninth symphony

was later added to it as well.

In both cases the actual melody is without up-beat.

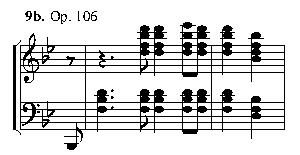

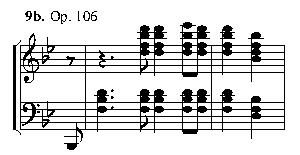

And a well-known instance is that of the interpolation

of the initial bar in the slow movement of Op.106,

where the dominant is indicated by the note C sharp;

Of the effect of this one bar, F. Ries (Leitzmann,

I, p.76) tells us: 'A very striking thing, from the artistic

standpoint, happened in the case of ... Op.106, which,

when engraved, is 41 pages in length ... When the

engraving was finished, and I was daily expecting a letter

fixing the date of publication, I got one with nothing

in it but the following remarkable instruction, "at the

beginning of the Adagio" (which, when engraved, occupies

9-10 pages) "insert these two notes -

|

I was to add two notes to a work that had been elaborated

in every detail and finished six months before.

But I was equally astonished at the effect these two

notes produced.' It is not mere chance that, among the

examples Riemann gives in the chapter on 'curtains',

Beethoven's later works are especially numerous: it was

only in his more mature years that he became such a

master in the art of creating the right atmosphere by the

simple device of using an up-beat containing the

dominant chord.

|

The re-shaping of the up-beat in Op.22 (Ex.3)

shows that Beethoven tried to avoid having an apex at

the beginning of the melody. We should not be justified

in drawing this conclusion from a single instance, but

there are other indications of the same kind.

|

We frequently find that melodies originally written without

up-beat, and having their highest note at the beginning,

were later modified by the introduction of an up-beat

in a lower register. The opening bars of the last movement

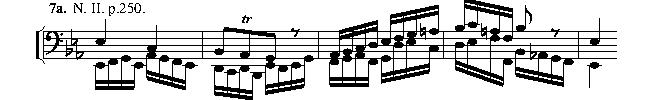

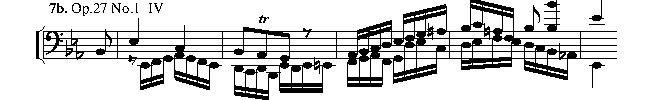

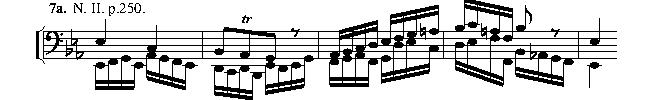

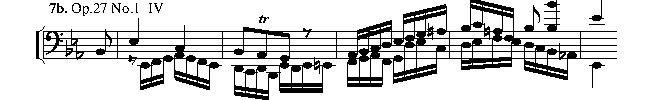

of the piano sonata Op.27. I will illustrate this:

The dominant up-beat B flat is added to the original

draft seemingly quite arbitrarily.

It is interesting to notice also that in none of the concluding sections

of this movement is the up-beat quaver treated in an unusual way

- a clear sign that it was inserted afterwards;

and often in the course of the movement the theme comes in without it.

|

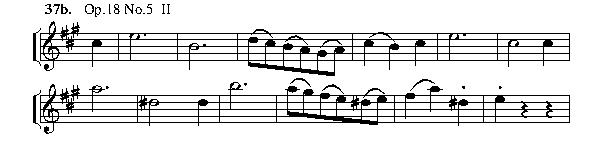

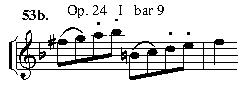

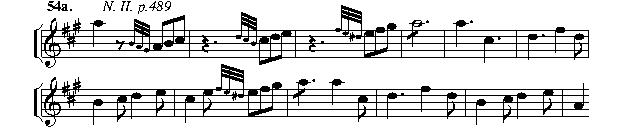

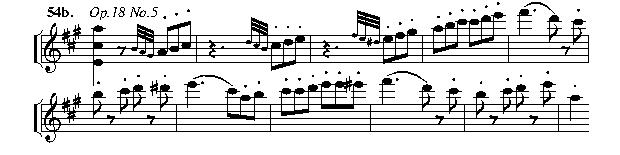

The alteration on the melody of the

variations in Op.18 No.5 belong to the same category;

By avoiding the first, schematic form of the melody,

the highest note came near the beginning; in the later

Working-out, where the thematic material is otherwise

very similar, an up-beat was inserted first.

|

The alterations in the opening themes of the sonata Op.106 and

of the quartet Op.131 show the same thing.

|

In Op.131 (Ex.10), probably on account of the

chromaticism, it was important to prepare the way for the

apex even more effectively than was done in the sketch.

(See also Ex.33).

And the addition of the 'curtain' to the slow movement of Op.106

(see p.9),

may have the same object. In all these examples, the intention is

to avoid beginning with the highest note of the melody,

which might too easily be felt as the climax.

The beginning of Op.106 (Ex.9) shows this clearly.

Nottebohm also was struck by the change in the second theme in the

last movement of Op.53. The crotchet C became repeated quaver,

and from that the actual up-beat was derived.

The change in the mood is especially clear in this example.

At the same time, in this theme he avoids a halt in the melody

and the obvious effect of the repeated note by

a breaking up the first crotchet into two quavers, and by

the caesura after the first quaver, as the result of the up-beat.

A halt in the melody may be produced by a rest,

and Beethoven prefers to change such pauses into a up-beats.

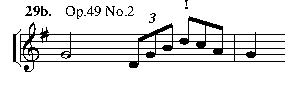

The second theme in Sonata Op.10 No.3 illustrates a case of the kind:

In this example also the apex of the melody comes early.

In other places Beethoven merely fills in the rests

and does not add the up-beat at the beginning.

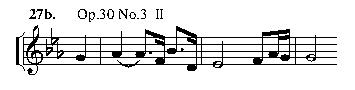

Thus, in the violin sonata Op.30 No.3.

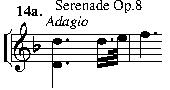

The same thing is beautifully illustrated in the threefold

recurrence of the adagio melody in the serenade Op.8,

and in the first theme of the rondo of the string trio Op.9 No.2.

But it should be noticed that, in the last example from Op.30 No.3,

the apex of the melody

is placed further from the beginning than in the previous ones.

The three repetitions from Op.8:

show admirably the development towards an increasing

dominant-tendency in the up-beat.

To the same category belongs the up-beat to the second part of 'Adelaide',

the late addition of which surely no one would have suspected.

Here also it is obvious that Beethoven intended to

fill in the second rest, and so was led to the up-beat.

The up-beat does not correspond to the rhythm of the

verse; further on, I shall frequently have occasion to

point out such 'instrumental' influences in the vocal

music.

A phrase from the theme of the funeral march

of the Eroica shows the same thing, and something

additional. Originally the phrase ran as in Ex.16a. In

a later sketch one up-beat was introduced (Ex.16b), no

doubt merely to fill in the rest. But this meant that the

two sequences were now different; in the final version

an up-beat is inserted in the middle, and, in a higher

register, repeats the first up-beat in intensified form.

Among the reasons for introducing the up-beat here

is the intention of getting greater roundness and

symmetry into the form.

Many further examples can be brought to illustrate this point.

The second theme of the first movement of the violin sonata

Op.30 No.2 originally had the form Ex.17a;

the next form (Ex.17b) introduces the up-beat when the theme

(expanded now from four bars to eight) is repeated;

and thence the final reading sets it directly at the beginning.

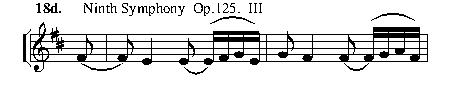

We must interpret the elongation by syncopation of

the initial quaver in the beautiful andante melody of

the slow movement of the ninth symphony as having,

formally, a similar significance; for each bar overlaps

the next with an up-beat (semiquaver or quaver).

This syncopated up-beat results in the syncopated binding

of the bars that follow, and repeated notes are thereby avoided.

An experiment following the above in the

sketch-book shows that Beethoven actually had this

avoidance in mind (Ex.18c). But it destroyed the

peaceful beauty of the passage: the solution finally

selected is undoubtedly both the simplest and the

richest in feeling.

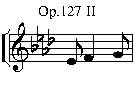

The theme of the A minor quartet, Op.132, is an

instructive example of how the up-beat character of the

later segments has an effect in a backward direction.

At first the sketches (Ex.19a) show it without initial up-beat;

it is obvious that the later bars have an up-beat.

Then at the beginning it acquires an up-beat (Ex.19b);

in the next sketch this up-beat is cut out, with a sequential

continuation (Ex.19c); in a later experiment (Ex.19d),

the second part of the sequence again has an up-beat

- the pause on G sharp was obviously too long.

Finally, the last reading (Ex.19e) reverts to the first plan,

but the beginning is given the force of an up-beat.

I consider that the instances cited (and I might give

many more of the kind) show that Beethoven added

up-beats to the original ideas for the following reasons:

to avoid repetition of notes, to prepare the apex of

the melody, and to clarify and round off the form.

To what degree this was conscious or unconscious does not

concern us here: all we have to do is to demonstrate the fact.

These phenomena fall into two classes;

in the one, the principle and object is the alteration of the melodic line;

in the other, it is the shaping of the form.

The distribution of the up-beats contributes to the establishment of the form,

and their dominant character brings out the tonality more clearly.

The beginning of the trio in the eighth symphony (Ex.4)

constitutes thus a much better cut between the main movement and the

trio than it would without an up-beat: the form is made much clearer.

These two aims appear again and again in a number of alteration groups.

As the next peculiarity, let us deal with the position of the melodic apex.

(b) The melodic apex and its treatment.

The position of the melodic apex is of great importance

for the effect of the melody. Naumann

(Emil Naumann,

Darstellung eines bisher unbekannt gebliebenen

Stilgesetzes im Aufbau des klassischen Fugenthemas, 1878.)

has demonstrated certain laws bearing on this point - for instance,

as regards the ancient classical fugue theme; and I

have been able to confirm and apply these rules to

a particular instance (the fugue based on the name of

Bach).

(Die Kraft des Themas, dargestellt an B-A-C-H, Bach-Jahrbuch

1922, p.14.)

In the present connection I take the apex to be,

not the highest note of the whole melody,

but merely the highest note of a large portion

clearly delimited by sequence or cadence;

unimportant auxiliary notes, grace-notes, etc. may be higher still,

though for the most part these are only seconds.

In comparing the sketches, several types of treatment

can be demonstrated, by the aid of which Beethoven

devised an effective position for the melodic

apex. In Part I we have seen examples showing how,

by its tension, a lower up-beat, usually in the dominant,

prepares the way for the apex (Exs.

3,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11).

It was Beethoven's custom to strengthen the thematic

material and effect of early apexes by immediate repetition

of the first motive, often in a higher register.

The technique of the sequences in Beethoven's melody

is one of the points already most often noted,

and we shall go into it in detail later on.

The sequences under notice are remarkable for their brevity,

and consist almost exclusively of two segments.

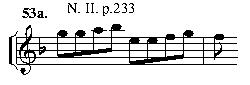

A characteristic example is the beginning of the violin sonata Op.24,

which has the highest note coming first with a one-bar sequence.

The rondo melody of Op.22 (Ex.3) also belongs here:

with the change in the up-beat the apex was removed from the beginning;

there is a two-bar sequence.

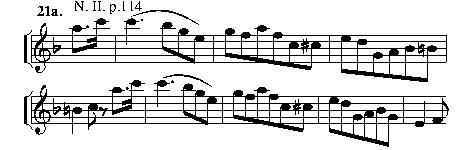

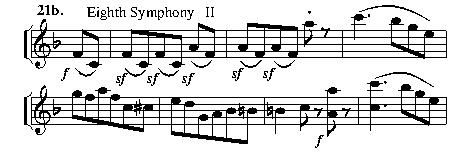

Ex.21a gives the minuet melody of the eighth symphony

as first sketched. Two things were altered, which

have relation to the high note's position so near the

beginning. Here, where we have to do with the eight-bar

song type, we can scarcely speak of a repetition of

sequences; nevertheless, a strengthening is constantly

effected in this way. At first the apex lay in the

up-beat: that was changed. And finally an ascending two-bar

'curtain' was also inserted.

Ex.21b gives the final version. It is easy to find

numerous instances of the kind in the completed works.

Of greater importance to us here are those places in the

sketches where the actual steps towards such repetitions

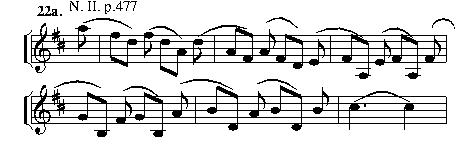

are elucidated. In the first draft for the presto

melody of Op.18 No.3 (Ex.22a) the theme opens with

the high note on the unaccented part of the bar; the

movement is so quick that the effect of the sequence of

the first four half-bars is not great.

The final reading (Ex.22b) shows the progress to

the short sequence of two segments of four bars, as

a result of the tempo. In addition, the high note is

repeated in the accented part of the bar.

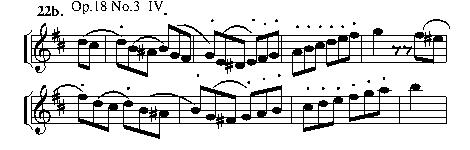

The alterations in the finale of Op.59 No.2 follow the

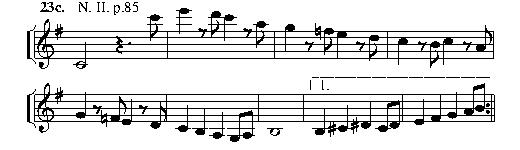

same tendency. The two first drafts (Exs. 23 a and b)

have the high note at the beginning, and no repetition:

a later one (Ex.23c) has the curtain placed low,

but there is no repetition: the final reading (Ex.23d)

has both, and the repetition is strengthened by a

sequence.

The development of the scherzo melody of Op.106 is also important for

our consideration later on. We see here (Exs. 24 a and b) how the sequences,

originally of two bars, become changed into one-bar sequences, and the

numerous attempts to alter the up-beat (Ex.24c) aim at accentuating the apex.

The unusual inversion of the melody in the finale of the Trio Op.1 No.2

(but see also Ex.23)

seems to me most simply explained as an attempt to avoid the early apex.

In view of this example, I consider the statement justified that the melodic

climax, when it occurs early, is often led up to by short sequences.

Undoubtedly energy radiates from a melodic apex;

but the apex must be given opportunity to take full effect.

The progress from the sketches to the final form shows a twofold aim:

firstly, to raise the apex definitely above the adjacent notes,

not to give it out just before or just after these.

The case of the eighth symphony (Ex.21)

shows the separation from the up-beat of an anticipatory high note.

In cases like this I shall speak of 'isolation' of the apex.

But it must come where there is a marked rhythmic emphasis, i.e.

in the accented part of the bar. The instance just cited

will serve as the first illustration of this.

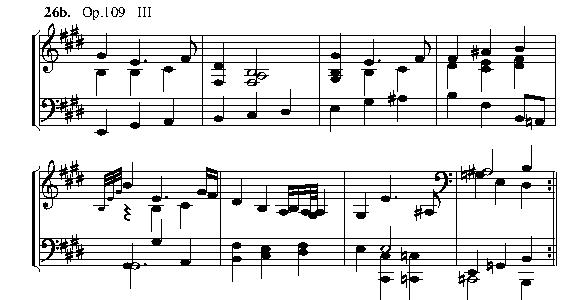

Perhaps the theme for the variations in sonata Op.109 is unique as

regards the simplicity of the alteration and the splendour of its effect.

The immediate repetition of the opening theme with early apex is clear.

The climax of the whole melody is B natural;

the sketch has this note in the most unfavourable position,

in the third beat of the fourth bar, i.e. as the last note of the first half.

How different is the effect in the final draft!

The apex, B natural, appears at the beginning of the second half,

and strengthened by a harmonic anticipation.

The tempo di menuetto of the violin sonata Op.90 No.3

also places the most effective apex, A flat, in the first part of the bar,

and puts a lower up-beat before it.

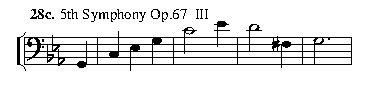

Two sketches and the final reading of the third movement of the

fifth symphony are distinguished from one another

solely by the position given to the group forming the apex.

With reference to the second of these sketches,

Nottebohm remarks: 'The pulse which the theme with

its rhythmic tendency to a two-bar structure requires

is more impressive just at the entry than would appear in print.'

The opening bars, which doubtless were at

first conceived merely as a curtain, hold the main

interest and force back the apical group. This actually

falls (if we think of it as in double bars) on the fourth

bar, which has but little rhythmic stress. That was the

reason for the removal of the opening bars: the shortening

of the C is less important, and indeed does not

occur in the repetition after the trio. It was not that the

curtain was 'superfluous ballast', but that it masked the

effect of the apex. In the other sketch, the opposite

experiment was made. The apex appears without a real

up-beat, in the unaccented part of the bar (double-bars);

and coming so early in the theme, it is much too short

to be effective in this quick tempo, unless there is

repetition. The final reading avoids both these mistakes.

The idea of double bars is not so compelling, the group

forming the apex is lengthened, and is prepared by an ascent.

It would be difficult to find a better demonstration

of the importance Beethoven attached to the position

of the melodic apex.

Without discussing them, I shall add a few simpler and less important examples,

illustrating how, even in these, the same principle holds good.

The apex may be isolated and brought out in several ways.

Ex.31 shows how, as compared with sketch a,

the final form b lengthens the chief note of the apex.

From sketch c we may possibly conclude that here

Beethoven intended to devote the accented first part of

the bar to the apex: in any case, the disposition within

the bar-lines is not quite uniform. The final reading,

b, syncopates the lengthened apex over the first bar-line.

In another instance I have shown that, in certain

circumstances, this kind of tension produces a greater stress.

(P. Mies, 'Goethes Harfenspielgesang "Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt"

in den Kompositionen Schuberts, Schumanns und H. Wolfs', Zeitschrift

für Aesthetik und allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft, Bd. XVI, p.384.)

In another group of alterations the apex is isolated by very long leaps,

occurring either immediately before or immediately after it.

This type figured very prominently in

Emil Naumann's study.

The scherzo melody of the Violin Sonata Op.96 shows this treatment

in the seventh and eighth bars.

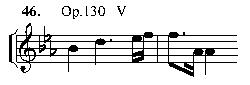

The cavatina of the quartet Op.130 was evolved exactly in the same way:

the apex in bars 4, 5 and 6, set gradually higher and higher

- C, E flat, F - is made more and more obvious by the drop that follows.

The beginning of the quartet Op.131 shows the same thing,

as well as the addition of the up-beat (Ex.10).

Finally, the apex may be isolated by adjacent notes

in unaccented parts being shortened or removed,

so that their effect is diminished or eliminated.

The following contrast shows this clearly: the high notes E and F,

which at first interfered with the apex, are abbreviated in its favour.

The theme of the scherzo in the Cello Sonata Op.69

is a very instructive instance. The first sketch (Ex.35a)

has, it is true, an isolated apex; but the complete parallelism

of the four-bar segments is disturbing.

The second sketch (Ex.35b) improves this; but

now the descent from the apex is impeded. The final

reading does away with this fault, and sets the second

cadence in sharp contrast with the first.

Becking,

in his remarkable study (p.137), has discussed the importance

of this change for the scherzo character of the theme.

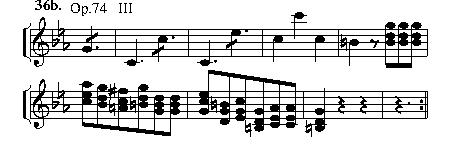

In the sketch (Ex.36a) for the quartet Op.74 the melodic line ascends

in both the half-periods; in the final reading this is changed

to a consistent ascent to the apex in the middle of the melody,

and a descent therefrom.

This form may be represented diagrammatically thus /\

and so is reminiscent of the typical classical fugue theme

(Emil Naumann,

op. cit., pp.13,17.).

But though Naumann (Op.cit., p.44.) has shown that

the converse form (beginning with a descent) is almost

unknown in the classical fugue theme, it is to be found

in Beethoven: I have already given instances of it.

In addition to the peculiarities of these themes, with

apex at the beginning (lower up-beat, sequence, or

repetition), there is often yet another; towards the end of

the theme is introduced a second apex, which balances

the first, and the way for which is carefully prepared by

sequences or special ascending forms. The diagrammatic

construction would be the reverse of the one

in the sketch, namely \/. It is very characteristic

of Beethoven that, at the same time, the first apex is

often prepared for in like manner.

The melody of the minuet in Op.18 No.5 shows this very beautifully:

Here a three-fold sequence introduces the apex, B natural.

Jalowetz (p.472) makes the statement:

"It is also characteristic of the technique employed by Beethoven

to get melodic intensity that at the close of a piece

he repeats a theme exactly, up to a certain point; but

then, where in the first form of the theme the melodic

line began to descend, he now adds another apex, and it

is only after this that the melodic line finally declines."

This development has already been traced here in the

first arrangement of the theme: the sketch still shows

the normal melodic form; the final reading creates a

balance between the apexes.

The theme of the andante cantabile in the quintet Op.16

shows a similar transformation in the second part. The second apex

D in the sketch, which, in spite of sequences, is unjustified,

is finally attained by a melodic line preceding it.

Whereas the transformation of the first half of the

scherzo theme in Op.106 (Ex.24) enhances the

sequence, the purpose of the second part is to bring in

the second apex steadily and smoothly.

As the next example, let us put side by side the beginning of the

violin sonata, Op.24 from a sketch and in the final

form: they require no further discussion.

From the foregoing instances, I think we may

confidently conclude that Beethoven seldom placed an

apex at the beginning of the theme, and considered

that apexes always required special introduction and

special treatment; a survey of his completed works

confirms the inferences drawn from the sketches.

And at this point we must make a further inquiry - i.e.

how far, in these style determinants, it is a question

of peculiarities of Beethoven's own, and to what extent

he shares them with other composers. To follow out

this inquiry in detail is beyond the scope of the present

book. When Gal (p.68), comparing similar themes by

Mozart and Beethoven, shows that Mozart set contrasting

parts side by side, whereas Beethoven used sequences

even in the construction of the melody, we

may conclude that in Mozart it is rare to find the initial

apex led up to by a sequence.

A survey of Brahms' early pianoforte works (Op.1-5) shows, for instance,

that, unlike Beethoven, he wrote a large number of

melodies that descend from the beginning, without up-beat

or sequence, and have a very different structure.

The theme of the andante in the quintet Op.16

(Ex.38) resembles in character the andante theme of

Brahms: piano sonata Op 5; here also there is an apex

at the beginning, but it is quite differently constructed

from Beethoven's.

In many of the foregoing points concerning the melodic apex,

I consider that unquestionably we have to do with

characteristic features of Beethoven's style;

for they must have had vital influence on the expressive force

and the effective distribution of stress.

My short remarks are intended to strengthen this view,

at any rate to some extent.

In my study of the songs of Brahms (Op. cit., p.177 et seq.)

I have shown that the melodic forms which, as their name 'ornament'

suggests, have often been understood as mere external decorations

of the melody, fulfill important functions in expression.

Here we were able to draw from the idioms employed in the vocal music

conclusions as to the instrumental music.

In the present study this possibility is, of course, very limited.

But once our attention is turned to the melodic apex and the way in

which it is brought out, it is natural to investigate special cases,

such as that from Op.109 (Ex.26); we pointed out

how the apex is emphasized there by means of the arpeggiated chord.

Thus Nottebohm was wrong in describing as 'ornament' an important note

in the theme of the Waldstein Sonata Op.53. I refer to the grace-note

C sharp, in the fourth bar, a note not present in the sketch (N.80, p.59).

The real explanation is simpler but less superficial.

The first apex, G, in the third bar, is steadily prepared for by

the progression E-F sharp; the following bar, a sort of repetition,

has nothing to set against this but the higher pitch.

So the grace-note serves to strengthen the apex;

if it appears only in the final draft, it does so not

as mere ornament, but in order to give more emphasis.

It is not difficult to show that turns and similar elements,

whether written out in full or not, have merely

the purpose of emphasizing the climaxes and apexes. On

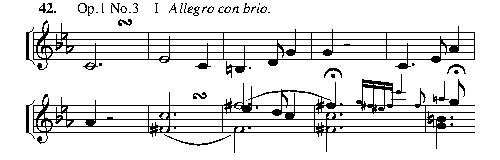

pp.70 and 88 Gal gives us information about elements

of this sort. But I cannot support him unconditionally

when he says, referring to the beginning of the trio in

Op.1 No.3: 'That the turn at the beginning is purely

ornamental is obvious from the fact that the string

instruments playing in unison with the piano do not have

it in their parts.' To my way of thinking, there are

quite different reasons for this. Whoever has played

the similar opening of the clarinet trio by Mozart (K.V.

498) must have noticed how difficult it is for the

instrumentalists to execute this figure simultaneously, in spite

of its being in strict rhythm.

Moreover, the string instruments have at their disposal certain dynamic

effects, such as crescendo and vibrato on the note,

which give the same sort of result as does the turn on the piano.

No doubt Gal is right in saying that these figures

are very stereotyped, especially in the early works.

But even in these, there are cases where they belong unconditionally

to the melodic line, which, without them, would

have quite a different effect: as an example, let us

consider the first theme of the C minor quartet Op.18 No.4.

In bars 1 and 3 we have to do with a subdual of

the thirds C->E flat, F->A flat, which allows the short,

transcient apexes E flat and A flat to be emphasized.

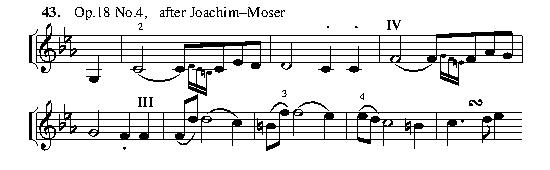

The writing of the theme for the violin in the Joachim-Moser

edition shows how the player, by means of changes

of position, introduces in the fifth and sixth bars the

same sort of effect by means of the leaps F->D, B->F.

I quote here two more examples from the early works:

(1) a simple one from Op.13, where the grace-notes

in the fifth and sixth bars help to raise the line, A flat->G,

of the highest notes:

(2) In the theme from Op.2 No.3 (Ex.45) the turn in the

first bar is meant to correspond to the ascents C->F sharp,

B->A flat in the third and fourth:

to get this effect, the melodic ascent in seconds in the

first bar would not be sufficient.

In the later works Beethoven succeeded in making this preparation

with greater variety and force. The beautiful line in bars 20-21

of the cavatina in Op.130 has the same basis, but the

figure is rhythmically matched to that of the first bar.

The grace-note at the beginning of Op.135 seems

merely to prepare the initial apex.

And the trill in the up-beat in the main theme of the

sonata Op.96 has the same force.

The repetition of the motive in the last two examples

confirms what has already been said. In all these

cases, and in innumerable others, we really cannot speak of ornament.

Strengthening the expressive effect of melodic apexes

is a peculiarity of Beethoven's manner.

In the early works it is associated more or less with a structural feature

in the style; later on, it becomes more complicated and forceful.

Schmitz (p.73) has also emphasized the importance

of the turn as motive in Op.18 No.1.

Of interest are some cases in which the original melodies,

shaped in accordance with the above instrumental principles,

are altered in the vocal works to suit new expressive requirements.

We shall consider this more fully in a later section.

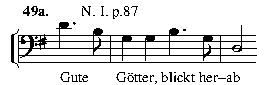

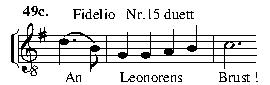

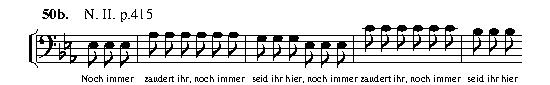

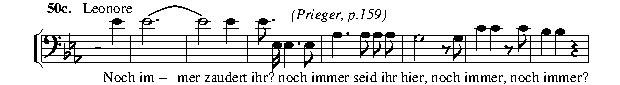

The fragment of an early opera contains the germ of the great duet in the

'Leonore'. Ex.49a gives the beginning of the episodic phrase:

The initial high note involves the repetition.

Ex.49b shows the corresponding part in the sketches for the

'Leonore', with the same structural form.

This descending formation in sequences was found

inadequate to express the joy of the husband and wife at their reunion;

the melody, constructed on instrumental lines,

was altered to correspond closely with the feeling of the words (Ex.49c).

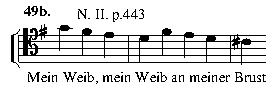

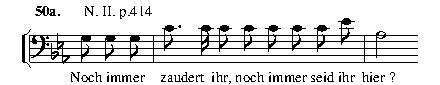

A similar thing appears in the sketches for the entrance of Pizarro:

The sketches show the instrumental sequences clearly;

they consistently contradict the feeling of the passage.

Nottebohm is right in considering them suitable for a 'jackass'.

How different is the 'Leonore'!

It is true that an apex like this at the beginning would be

almost impossible in Beethoven's instrumental music;

and here there is actually a second one, well prepared,

which in some degree supports the first.

Such passages show how attentively

Beethoven allowed the feeling of the text to influence him,

and how he tried to follow it, sometimes against his own usual practice.

(c) Repetition of notes.

In the first section I have already given a number of instances in which,

by alteration, Beethoven avoided repetition of notes in the melodic line.

Such repetition tends to bring about a sort of melodic stagnation.

Many of Haydn's themes, with their gay and naive melody,

have, as Gal (p.85) has pointed out,

a tendency to repetition of notes which comes direct from folk-song.

"In thematic construction of this sort,

the undeniable melodic weakness is balanced by rhythmic vivacity.

The mature Beethoven, striving to make his musical ideas as concentrated

as possible, was naturally obliged to discard this technique,

just as he was obliged to discard the mannerisms of Mozart's style.

In the youthful Beethoven, those mannerisms are to be found chiefly

in cantabile passages, to which Haydn's technique,

as we have aready seen, would scarcely have been applicable."

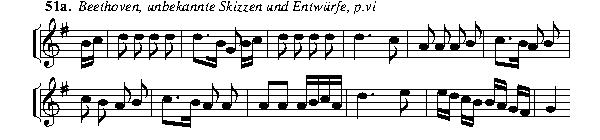

Accordingly it would be of great interest to find instances

in which the one mode of expression is converted into the other.

There are indeed such passages,

among them the following unused draft with alternative

(Veröffentlichungen des Beethovenhauses Bonn. III. 1924.

Beethoven, Unbekannte Skizzen und Entwürfe, p.vi.):

The alternatives come in at the places where there are

conspicuous repetitions of notes.

How much better the final reading with its harmonized suspension

fits in with the character of the remainder of the melodic structure

than does the fourfold note-repetition of the sketch !

The opening theme of Sonata Op.24 given in

Ex.39

likewise substitutes suspension for the repeated note in bar 9

(compare Ex.53 and Ex.39b).

By this means the flowing melodic structure of the

other bars is continued in an even stream, which

undoubtedly has contributed to the name 'Spring Sonata'

(Thayer, ii, p.247).

And the bars, already referred to,

in the rondo of Op.22 (Ex.3) become more soft and

flowing through the introduction of suspension; progressions are formed.

In other places progressions without suspension are

substituted for repetition of notes. Compare the 'soaring'

continuation of the theme in the quartet Op.18 No.5

with the curious stagnation of the sketch, or the altered

up-beats in the sonata Op.90 (Ex.1), and in the second

part of the song-cycle (Ex.2).

The example from Op.90 also shows how the rest is filled in

by a repetition of notes. Even this is not just chance: in

a later Section (Chapter II g)

I shall explain it as one of the determinants of Beethoven's style,

employed to produce a quite definite effect.

Gal's remark about the 'naive gaiety', like that of a folk-song,

produced by note-repetition, would apply especially to the sketch

for the G major quartet Op.18 No.2 (Ex.55a):

By rhythmic-harmonic enlivenment and slurring

something quite different is produced (Ex.55b).

The sketch could never have given rise to the name

'Compliment Quartet'

(Th. Helm, Beethoven's Streichquartette, p.12);

for this demands something graceful and gallant rather than naive -

"the idea of the festive opening of some reception-hall (in the rococo

period, of course), and the ceremonious presentations

and reverences that follow".

The last examples are peculiarly suited to show how

limited in their scope alterations in the melodic structure

often are, and how great the change in feeling

associated with them may be. And we see that the

element producing naive gaiety is repetition of notes;

whereas elegance and grace, such as cantabile passages

especially require, are effected by suspension. This has

often been pointed out before, of course; but seldom

has an opportunity offered to see so clearly how

the feeling underlying the whole intention seizes on

unsuitable portions of the melody, and proceeds to reject,

alter, and unify them.

(d) Suspension: absolute melodic structure.

In dealing with another peculiarity of Beethoven's style I can be brief -

partly because I have already said something about it in the preceding pages,

and partly because Gal has studied it in detail.

I refer to Beethoven's treatment of suspension.

On this subject Gal (p.60) says:

"No melodic notes foreign to the chord are used

except regular changing notes and diatonic passing

notes in the unaccented part of the bar.

Suspension is excluded, and so is chromatic progression."

Gal gives a beautiful example from a sketch for the slow movement

of the fifth symphony.

He calls this 'absolute melody', and defines it (p.61) as

"a purely diatonically conceived melody, containing neither suspension

nor passing notes on the accented part of the bar".

In the works of Beethoven's mature years this is the rule;

it is the goal towards which the master, even while he

was still young, slowly and surely strove.

In the sketches there are few instances showing, as clearly as

occurs in the fifth symphony, the rejection of suspension.

Here we have to do with an idiosyncracy so characteristic

of Beethoven's development that eventually it seldom

became necessary to make any such change.

|

The sketches for the funeral march in the Eroica contain a very fine example.

Ex.56 shows the changes in the sixth and eighth bars.

Finally, in the eighth bar the suspension is entirely rejected:

in the sixth bar there is a change in rhythm

and especially in the harmonisation.

Gal has shown the same thing, and remarks (p.80),

"In this way notes originally suspended become independent harmony notes,

and gain proportionately in expressive force."

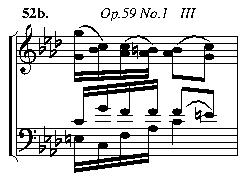

In the example from Op.59 No.1 (Ex.52)

I have already drawn attention to the same thing.

The almost ethereal effect due to the absence of suspension

is shown in a couple of bars from the adagio in Op.106.

Ex.57a reproduces the sketch, as follows, and

Ex.57b gives the completed work.

These chords without suspension appear in admirable

contrast to the crowded ones in the preceding bars

- a triumph of 'absolute melody'.

Naturally those instances are of interest to us where,

in contrast to the foregoing, suspensions are afterwards

introduced. As a matter of fact, this happens

more frequently; but the instances can be brought

together in a few groups and arranged under certain effects. Thus

in Chapter 1c

I have already mentioned the substitution of suspension for repetition of notes

(Ex.3, Ex.53)

in order to produce a flowing effect.

A second group has its origin in an endeavour to meet

the requirements of form. Here, as in cases previously

mentioned, up-beats are added so as to correspond to

up-beats occurring later.

The minuet in sonata Op.10 No.3 illustrates this in the sketch and

the final reading of bars 7-8: originally only the last bar of the

melody had this suspension. The result is a sort of musical rhyme.

To this group belongs also the development of the

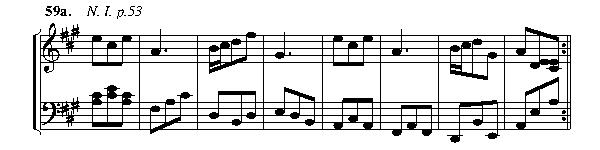

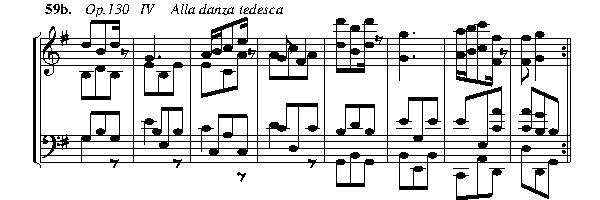

alla danza tedesca from Op.130.

A sketch in A major of the movement

was originally intended for the A minor quartet Op.132;

neither in the fourth nor in the eighth bar has it

the suspension it receives in the final reading;

only the second and third quavers in the eighth bar of the sketch

contain something of the kind.

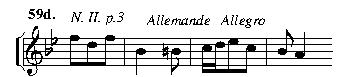

In a further sketch (Ex.59c) this flowing line has become a suspension

- indeed, as the final form shows, a fully harmonised one.

The fourth bar is missing, as if Beethoven were not

quite clear about it. A later sketch (Ex.59d) in B flat

major has the suspension in bar 4 also, but resting on

bar 3. It is only in the final reading, however, that one

gets the complete suspension in one bar independently.

The flowing line, then, was the basic idea. At first it

developed into the fully harmonized suspension in bar 3 ;

then for a time it was not so clear. And this involved

the suspension in bar 4, for the sake of symmetry.

What Gal has demonstrated is not affected by these

examples; in all of them the idea leading to the suspension

is perfectly obvious.

Twice already I have mentioned groups of alterations that

have come about in obedience to principles governing form;

for an understanding of the development of the melodic form,

comparison of the sketches and the finished works yields valuable information.

Continued in Part II: The melodic form

See also:

Index of Opus-numbers,

List of Abbreviations,

Bibliography,

Editor's notes

Also:

www.pjb.com.au,

www.pjb.com.au/mus