Translated by Doris L. Mackinnon as

Beethoven's Sketches:

an analysis of his style based on a study of his sketch-books

publ. Oxford University Press 1929, and Dover 1974

|

|

Fischer goes on to state (p.62): "In the neo-classical style, melodies, either of the S-type or closely allied to it as regards their form, are fitted into the frame provided by the baroque C-type." Or, somewhat differently expressed (p.52): "The C-type develops into the form of exposition of the sonata movement, with exclusion, of course, of the second section." Fischer (p.51) instances a theme by Pergolesi as an example of the transition, "where the first subject of a melody framed on the C-type is constructed on the S-type". Space will not admit of my dealing further with the matter here; I shall discuss the importance of these sections more fully in a later part of the book.

The definition of the two types of melody shows that repetitions and sequences fulfil an important role. And in Chapter I we have already dealt with these structures. So let us now consider the groups of alterations and those cases which have to do with the formation and arrangement of repetitions and sequences.

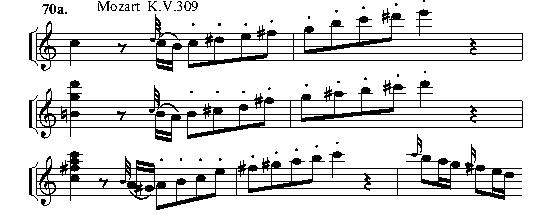

Gal (p.68) has shown how, in the episodic theme of the 'Coriolanus' overture, a four-bar group is formed by threefold repetition, and he has drawn attention to the logical way in which this is introduced. Later (pp. 111-12) he quotes similar instances of groups used in the working-out. As a matter of fact, it is possible to demonstrate this threefold repetition everywhere throughout the structure both of theme and of movement, and in their larger as well as in their more detailed aspects.

|

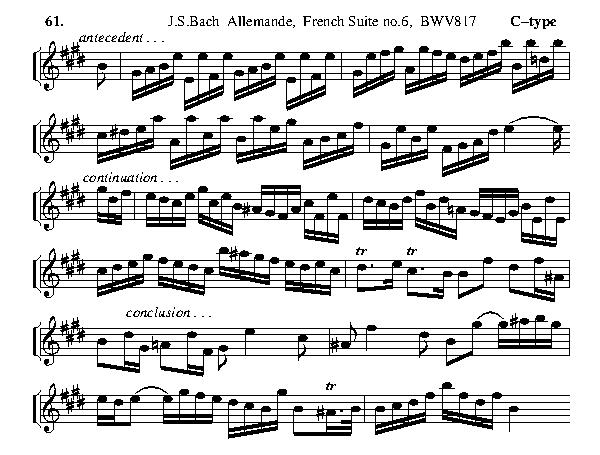

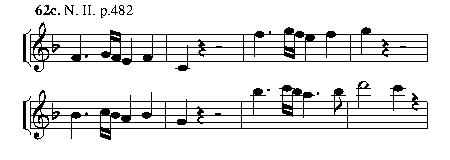

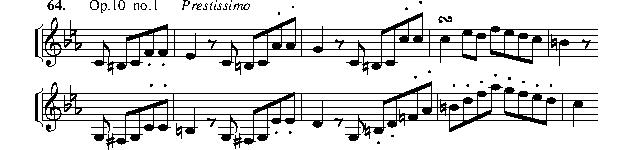

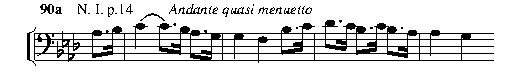

62 b contains a threefold repetition, but it is very 'short-winded'.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

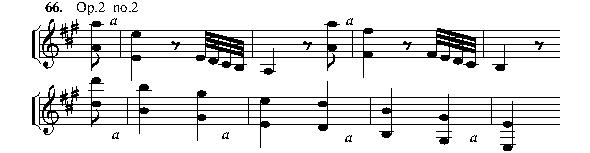

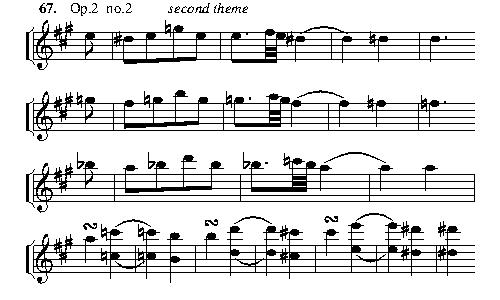

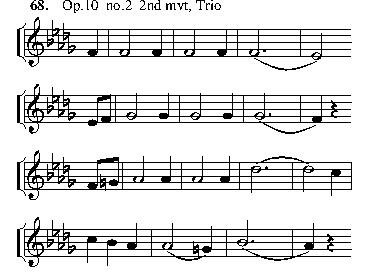

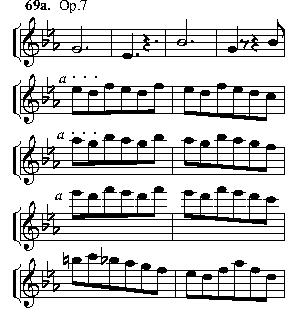

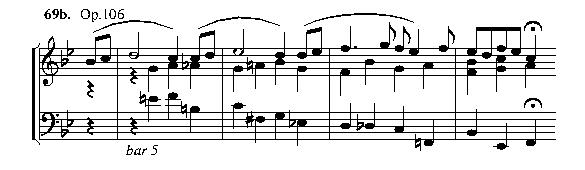

This melodic structure has certain disadvantages; it produces clear-cut caesurae at every two bars, which become inconspicuous only when the tempo gets rapid. In his early work Beethoven was satisfied with this structure; later on he used it only where it could do no harm. In the threefold repetition in thematic structure we have one of the stylistic features characteristic of Beethoven as a young man.

We learn something more, however, from these considerations. The S-type is usually in eight bars, and, so to speak, square; this follows inevitably from its origin in folk-song and dance tunes (Fischer p.29). But in Beethoven the C-types of melody also have the same number of bars.

|

|

|

|

As we have seen, threefold repetition served for construction of the theme; there are other cases where it is employed to build up a movement or a part of a movement. Gal goes so far as to interpret these threefold groups in the working-out as an attempt to 'expand the form' (p.113). In simple song-melodies we constantly find the threefold repetitions of a phrase, and especially of its first half; in the same way, it is very common to find a whole melody repeated three times in slow movements and in rondos. An instance of this occurs in the third movement of the serenade Op.8, where two melodies - adagio - allegro molto - adagio - allegro molto - adagio - appear alternatively; and the slow movement of the violin sonata Op.96 brings in the main theme three times. This can scarcely be regarded as a peculiarity of Beethoven's.

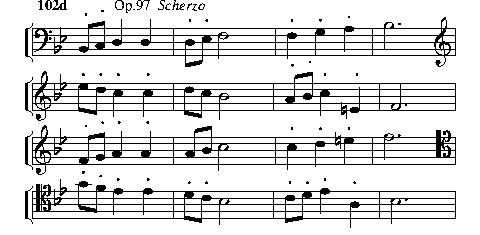

It is another matter altogether when we proceed to

follow out the development of this idea in cases where

the form has to be expanded in movements of minuet

or scherzo character occurring in the works between

Op.70 and Op.100 roughly. Here we have not so

much a special feature of the scherzo, in

Becking's

sense, as a middle section, We find a transition to this

in the scherzo of the pianoforte trio Op.97. The

first part of the scherzo theme consists of 16 = 2 x 8

bars; then follows the second part; and to this is

immediately appended the melody of the trio plus the first

part. The repetition-signs show that all this is to be

played twice; then follows the second part of the scherzo,

and after that comes the coda, which gives us the following

structure:

Part I |: Part II + Trio + Part I :| Part II + Coda

|---- Scherzo ----|

and this means that the scherzo melody occurs three

times. This form occurs in full in the presto of Op.74, in

the Presto of the seventh symphony, Op.92, in the trio

portion of the allegro assai vivace ma serioso in Op.95

(though with fundamental changes), and then finally

in the presto of Op.131. There have always been

minuets and other dance forms with two alternating

passages in which the main melody is repeated three

times. But to expand this form with an episode is

undoubtedly one of Beethoven's peculiarities as a

composer; and even in his work it occurs only for a relatively

short period. Later on, Schumann revived it in some

degree, when, as in the second symphony, the pianoforte

quintet and the third pianoforte trio, he expanded

the several parts; but he made a departure by introducing

two trios. This is an instance of the way in which

a composer of the romantic school dealt with and modified

the development introduced by Beethoven; in

Beethoven's own work the form is expanded, but the

thematic material remains unaltered; in Schumann the

material is expanded, and it is the form that remains

unaltered. Later on, as in the molto vivace of the ninth

Symphony, we get, however, some expansion of the

theme, in which fugato plays an important part.

In his earlier work Beethoven effected this expansion in other ways, as can be seen by comparing the octet for wind-instruments Op.103 with the string quintet Op.4. Altmann has pointed out (compare also Orel) that the quintet is not a mere re-instrumentation of the octet, but has been rewritten and expanded from first to last. The final movement of 223 bars in the octet, for instance, is extended in the quintet to 418 bars. This movement can be divided up into some four sections. In the following table the comparison is brought out:

| Op.4 | Op.103 | Difference | ||

| (a) | The first theme with its working-out and repetition | 164 | 90 | 74 |

| (b) | The middle section, up to the repetition of the first theme | 72 | 61 | 11 |

| (c) | Up to the re-entry of the middle section | 87 | 47 | 40 |

| (d) | The repetition of the middle section, and the coda | 95 | 25 | 70 |

| 418 | 223 | 195 |

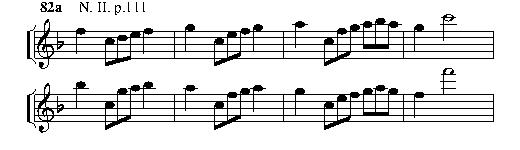

Writers have frequently laid stress on the importance of sequences in the formation of Beethoven's themes and elaborations generally. In addition to the passages already mentioned (in a certain measure the threefold repetition also belongs to this category). I shall refer to the treatment of individual themes in the third and fifth symphonies pointed out by Schmitz (pp.79, 84). I have already made it clear that this threefold repetition is a feature of Beethoven's early style.

|

|

|

|

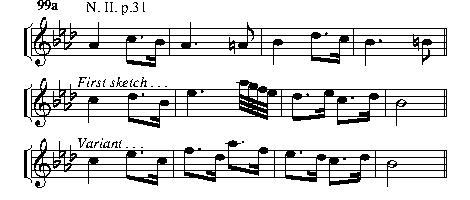

This association of repetition and sequences in the forming of a theme is a kind of logical construction from a motive provided by the imagination. Out of such a motive the construction promptly develops a theme, which has then to be modified in consequence of its too regular rhythm or of the predominance of sequences. I propose to deal more fully later on with the psycological aspect of this process: here I shall merely give a few more examples.

|

|

|

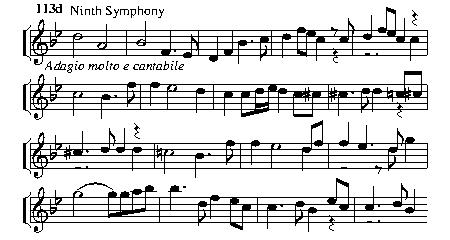

As we may judge from the sketches, the beautiful middle section of the adagio of the ninth symphony also suffered from too great uniformity of rhythm, a fault that was soon corrected by alteration of the melody in the third bar, together with addition of an up-beat and syncopation.

At the beginning of the second part of the march Op.45 No.1 we see how a series of short sequences is avoided through rhythmical and melodic changes in the first segment as contrasted with those that follow.

|

|

|

|

|

|

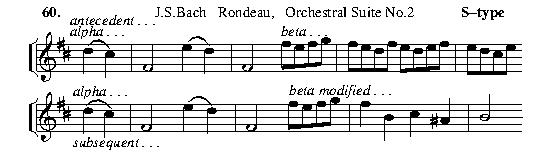

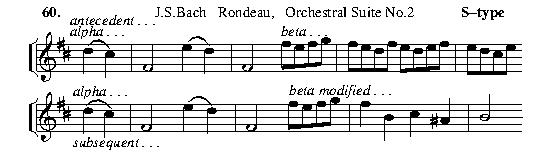

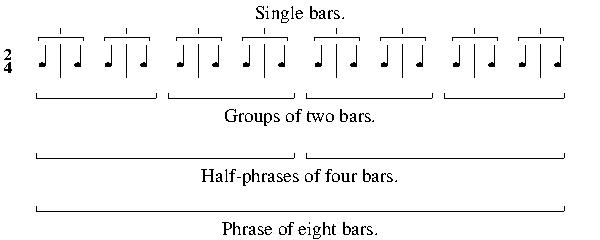

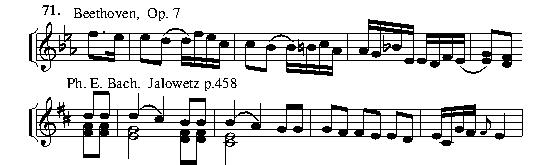

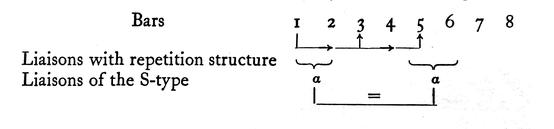

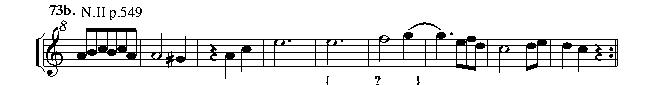

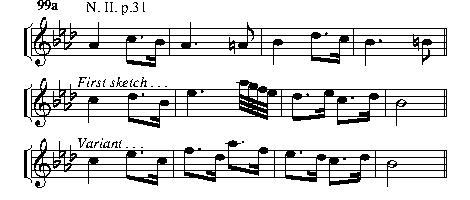

In other groups showing alteration of the structure of the sequences we see the development of perfectly definite types of melody. The essential feature in these types lies in the relations between the several parts of the melody. The example on p.47 shows what these are. The way in which they are grouped is characteristic of each type. In the S-type they follow in successive groups, the second linked to the first (H. Riemann); isolated parts of the melody, such as bars 1-2 an 5-6, are alike, both as regards motive and rhythm (Ex.60). The C-type is different; the successive parts are connected by virtue of sequences and repetitions. Fischer has shown that 'where the antecedent is made up of a number of segments, the motives of the sequences in the continuation are always shorter; as soon as the continuation begins, we get a contraction of the rhythm'. In what follows I shall refer to this phenomenon as 'sequence-contraction'. I consider that what is essential in shaping the form is to order the relations of the final melody in such a way that they suffice to unify it and make it hold together; but they must not be so numerous that the independence of the several parts is seriously imperilled: for this leads to the form's becoming unrecognisable. Ex.8 illustrates this. It is possible to find in the sketches a number of groups in which we can see a unified type of melody develop out of a condition in which there was a superfluity of liaisons consisting of sequences and regular rhythms. The theme from Op.132 (Exs. 6 and 73), to which I have aready referred so frequently, belongs here. From the first drafts it is not possible to ascribe it to any particularity of melody, either on account of, or in spite of, the rhythmic liaisons between bar and bar (Ex.6); it has a certain unity, but is not well put together. In its second stage (which, however, may possibly not belong to this developmental series) it is a C-type; there is a four-bar antecedent with two-bar liaisons, and at the end we end a Sequence-contraction. The next sketch (Ex.73b) has none of these organising liaisons; it is to be regarded merely as an eight-bar antecedent of a C-type which also has a course of eight bars. In the final form (Ex.73c), which is distinguished from the others by something additional ( See Chapter II g), liaisons are again established between bars 1, 3 and 6 by means of similarity in the rhythmical treatment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

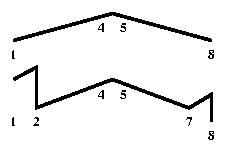

Elsewhere

(Zeitschrift

für Musikwissenschaft)

I have shown that it is not justifiable to

apply the concept of 'symmetry' to the normal S-type;

but here symmetry is actually produced, and might

be reproduced diagrammatically somewhat as follows;

The second sketch (Ex.23b)

is even more unusual; in this it is

impossible to recognise either the S- or the C-type.

Elsewhere

(Zeitschrift

für Musikwissenschaft)

I have shown that it is not justifiable to

apply the concept of 'symmetry' to the normal S-type;

but here symmetry is actually produced, and might

be reproduced diagrammatically somewhat as follows;

The second sketch (Ex.23b)

is even more unusual; in this it is

impossible to recognise either the S- or the C-type.

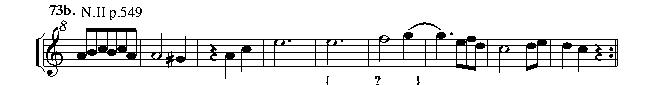

And we find that Beethoven also rejected this arrangement of the liaisons. What did he substitute for it? An eight-bar C-type with a four-bar antecedent (||: 2 :||) followed by a continuation of four bars showing sequence-contraction (Ex.81).

|

|

In the article referred to, I showed that it is possible to make music strictly symmetrical by technical means without our feeling corresponding to this in any way. The way in which these two almost symmetrical themes were altered, and the fact that really symmetrical melodies seldom, if ever occur, seen to justify my opinion and to give it the support of a very important witness, i.e. Beethoven himself.

Lorenz has shown that in the arrangement of Wagner's melodies there is a plan - a b c b a - and this he calls the 'perfect curve' (a, b, and c stand for the several melodies). But the fact that a structure so simple as this has escaped detection for so long is, to my way of thinking, just so much the more proof that no acoustic or aesthetic equivalent for it exists.

|

|

,

or by the ascending and descending seconds in bars 2, 4 | 5, 7.

In the final form, it is true, these liaisons are cut out,

the repeated motive is shortened by one bar (probably on

account of the early apex) and the triplication is added.

The concluding bar should really come then, but this

does not appear in the original form. lt was omitted,

and in its place there was added a further triplication

with an appropriate final bar.

Becking (p.141)

has already pointed out the importance of this irregularity

with regard to the scherzo character. This

seven-bar melody is undoubtedly a peculiarity, and

it can never be understood as an S-type, but as a

C-type in conjunction with threefold repetition. An

example like this shows that Beethoven was aware of

the superabundance of liaisons and sequences; the

quick tempo (double bars, according to Becking)

makes the rhythmical structure from bar to bar less

conspicuous.

,

or by the ascending and descending seconds in bars 2, 4 | 5, 7.

In the final form, it is true, these liaisons are cut out,

the repeated motive is shortened by one bar (probably on

account of the early apex) and the triplication is added.

The concluding bar should really come then, but this

does not appear in the original form. lt was omitted,

and in its place there was added a further triplication

with an appropriate final bar.

Becking (p.141)

has already pointed out the importance of this irregularity

with regard to the scherzo character. This

seven-bar melody is undoubtedly a peculiarity, and

it can never be understood as an S-type, but as a

C-type in conjunction with threefold repetition. An

example like this shows that Beethoven was aware of

the superabundance of liaisons and sequences; the

quick tempo (double bars, according to Becking)

makes the rhythmical structure from bar to bar less

conspicuous.

|

|

|

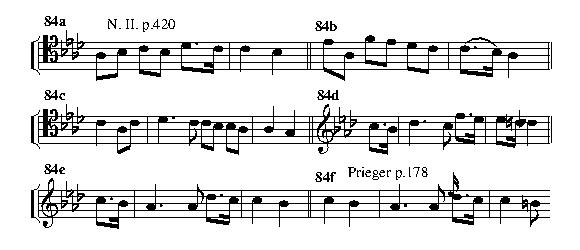

In Ex.83b an attempt is made to improve on this by a change in bar 3, without further justification.

In the final reading the two-bar sequences are cut out. Does this not involve a loss of structural stability? It is clear that Beethoven recognised that the sequences of the original form were to some degree logical, but the construction finally adopted is not quite sure, nor quite intelligible.

|

In the foregoing paragraphs I have dealt mainly with the excision of superfluous liaisons conditioned by the rhythmic structure or by sequences. I shall now refer to some cases in which the liaisons depend on similarities in the melodic structure. It is impossible, of course, to draw a hard and fast line between these and the preceding. All I am concerned to show is that Beethoven finally selected, from out the superabundant liaisons, just those which were characteristic of the particular type of melody adopted in the final reading.

|

|

And in this connection there is an interesting case (Ex.85) quoted by Gal (p.94) from the trio in the second symphony, where the melodic liaison in bars 5 and 7 is weakened, so that there remain only those belonging to the S-type.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 x 2 + 2 x 1 + 2 + 2 x 2 + 2 x 1 + 2

antecedent continuation, antecedent continuation C-types

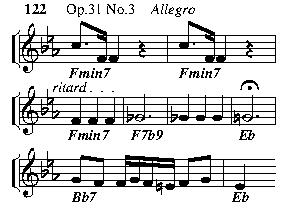

Antecedent CF7 Consequent CF7B6 of S-type cadences

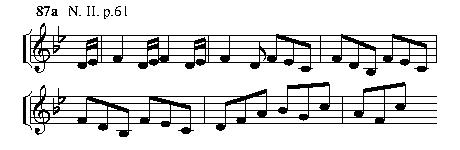

But even the first sketch (Ex.87a) foreshadows the introduction

of the Malinconia theme.

The above examples should suffice. We see in them clearly that Beethoven was striving after an intelligible and characteristic thematic form; but at the same time it is apparent that the completed form was not a flash of inspiration that came at the first moment, but the result of retaining a certain rhythmical and thematic structure throughout the many changes to which the work was subjected.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

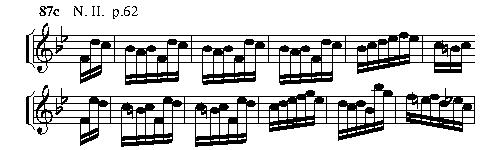

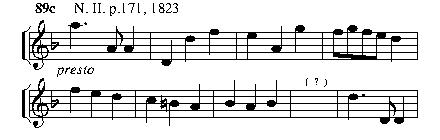

The beginning of a longer sketch (Ex.89c) shows a similar mixture.

Little by little, the raggedness of the beginning is smoothed away, the quavers disappear, and with their dissapperarance the melodic line hecomes better unified (Ex.89d).

From the sketch (Ex.89e) we may perhaps conclude that the idea of 'Ritmo di tre battute' was the germ from which this unification arose.

|

|

|

|

2x2 (antecedent) + 2x1 + 2 (continuation)

|

|

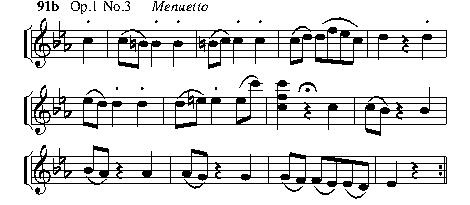

In the final form (Ex.91b) the first and second bars of the sketch are cut out, and as third bar a motive is introduced that corresponds with bars 7-8 in the sketch.

The outcome of these changes is a regular S-type

with a rest in place of the eighth bar. This S-type is the

antecedent of a C-type, and the whole theme has accordingly

the structure of a C(S)-type

(see abbreviations),

with the structure

2+2+2+1+fermata (antecedent) + 3x1 + 3x⅓ + 1 (continuation)

|

|

The finished work, on the other hand (Ex.92b), is definitely of the S-type; bars 1-2 and 5-6 are rhythmically alike, and the repetitions have dropped out.

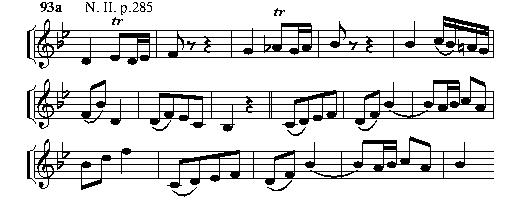

I have already pointed out (p.61) that I agree with Fischer on the importance of sequence-contractions as a term of melodic liaison. The relation of the length of sequence in the antecedent to that in the consequent, and the working-out of the contraction, are matters of vital importance to the elasticity of the theme in the C-type. In one group of alterations, where the theme may originally be of the S-type, the characteristic feature is the development to a C8, C16, etc.

|

|

2x2 + 4;

this was followed by an S8 as the second part.

In a later sketch this second part has already

undergone contraction.

From this, the final reading (Ex.93b) proceeds logically

on the plan 3x1 + 3x1 + 2.

The whole thing, accordingly, is a C, in which both

the antecedent and the continuation are also built on that type.

The small subsidiary half-bar sequences in the continuation are important to the development, which is completely lacking in the sketch, where the two types are merely set side by side. The special character of the form is in no way affected by the fact that the repetitions are varied in the two parts although the harmonization is the same.

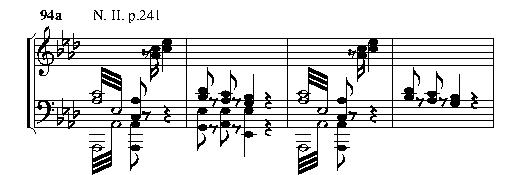

|

|

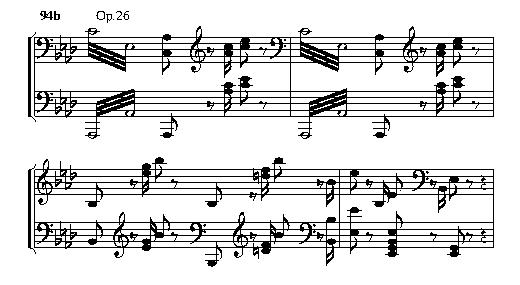

In the finished work (Ex.94b) this somewhat trivial regularity is replaced

by a C4 with wonderfully effective contractions. It is built as follows:

2x1 (anteced.) + 2x½ + 3x¼ (contin.) + ¼ (conseq.)

This effect is much employed in episodic sections.

|

|

|

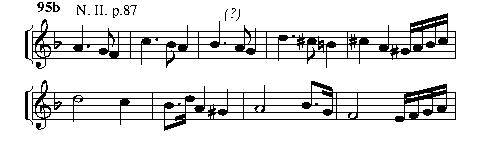

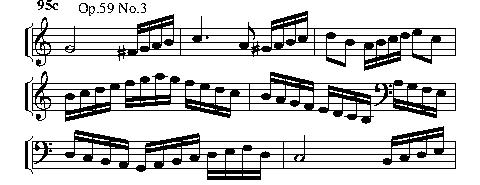

In a later sketch (Ex.95b) it began with a very short contraction. The theme still lacked development to the repetition.

This appeared only in the final form (Ex.95c), where a series of contractions lead up to the repetition with admirable inevitability.

|

|

|

|

|

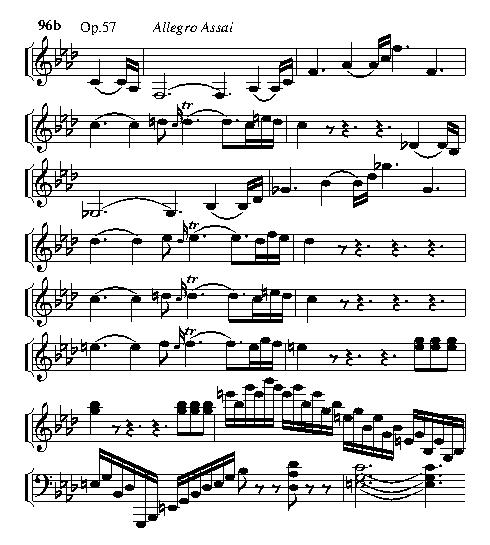

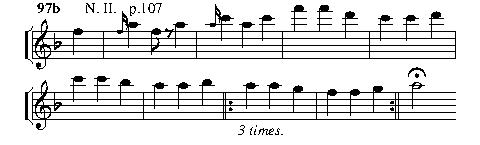

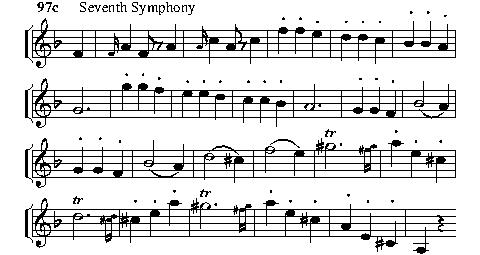

later on (Ex.97b) it consists entirely of two-bar segments without connection or development;

finally (Ex.97c), it becomes a boldly conceived type with the following

structure:

2 (curtain) + 4x2 (anteced.) + 2x2 + 2x1 (contin.) + 3x2 + 2 (conclus.)

which is 24 bars.

It is clear that Beethoven experienced some difficulty in developing

the form; but create it he did by sheer hard work, guided,

whether consciously or not, by certain definite principles.

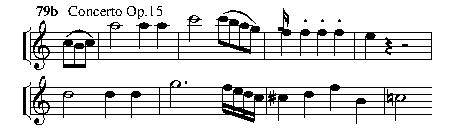

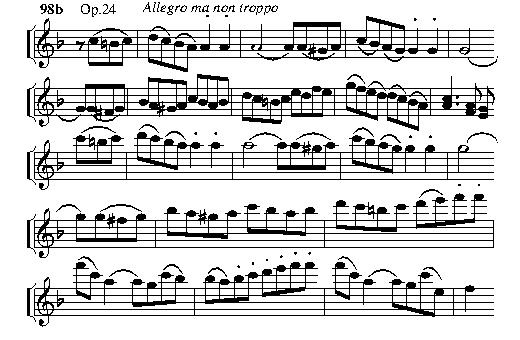

In these last examples we find the development moving towards more wide-embracing thematic complexes. Since Beethoven now preferred to begin themes with sequences, and since such structures tend to involve contraction, a type was produced that begins with a C8 and then repeats this with a change in the second part. The whole theme, therefore, is of the S-type, in which either the antecedent or the consequent, or both, are of the C-type. I have already referred to an S (C) of this kind from Op.18. No.6 (Ex.87). In Ex.91 from Op.1 No.3 we get the converse type C (S). Both were very common in Beethoven's works, and both tend to increase the complexity of the theme (the thematic complex).

|

|

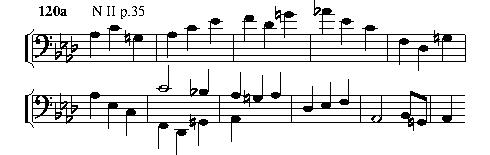

whereas in the final form (Ex.98b) it progresses from half-bar to quarter-bar sequences. The antecedent is a C8; by means of repetition, with altered and intensified cadence, an S (C) type of 18 bars is produced.

|

|

The final form steers clear of this defect and begins the continuation at once with the contraction and repeats the antecedent with a different cadence, so that the whole become an S (C) type of 16 bars. The fact that most of the S (C) types have an even number of bars does not follow as a matter of course; it is merely a consequence of what I have often mentioned already, i.e. the regular number of bars in the types of which it is composed.

|

|

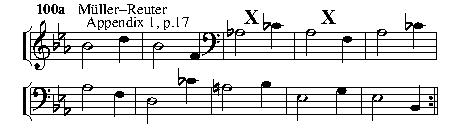

Ex.100b gives the whole passage. It is built up as

follows:

4+4+4+4+2+2+2+2

Interpolation of the two bars would make it:

4+4+4+4+2+4+2+2

Accordingly, the present solution seems to be the better

and more justifiable.

This suggests an interesting inquiry into the rhythmical construction of Beethoven's compositions in general, i.e. the way in which the larger parts are put together. But obviously such an inquiry would be beyond the scope of the present work.

All the foregoing examples show how the production of form may depend on the cutting out of liaisons, rhythms, sequences, along with the introduction of thematic connexions and sequence-contractions. They make us see the advantage of considering the question from at new angle, and, in place of studying the means by which the remodelling is effected, of demonstrating rather how the first ideas as they appear in the sketches are related to the final form they assume in the finished works, and to what types these belong.

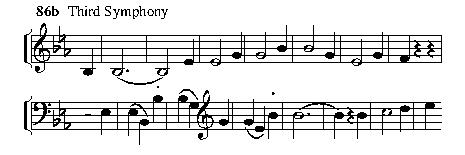

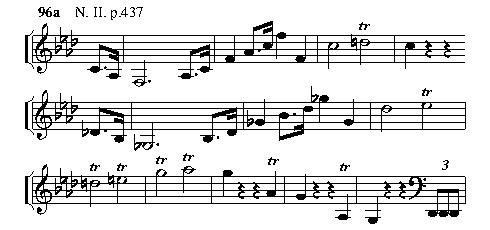

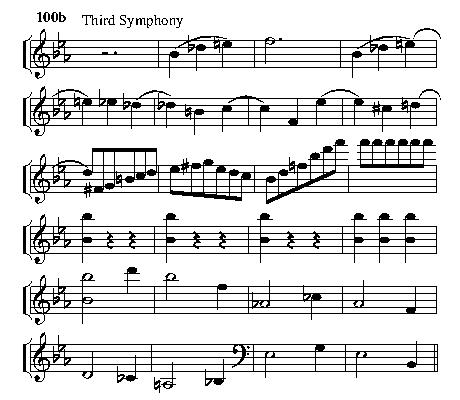

I propose to deal first with those themes which develop into an S-type. In Ex.92 I have already cited the adagio theme of Sonata Op.96, in which an S is derived from a melody with disconnected liaisons. In the theme of the theme of the Eroica (Ex.86) a varied S-type is developed from a simple one.

|

|

In the final reading (Ex.101b) the S-type liaisons almost disappear, or are, at any rate, profoundly modified - at this stage they cannot be completely destroyed. This theme shows Beethoven at his most typical; in a later section I shall discuss more fully the method by which the transformation is effected. The characteristic feature in this kind of melodic construction is the remarkable emotional breadth.

|

|

|

|

A second sketch (Ex.102b) written in the C-type has sequences in the consequent, but none in the antecedent.

A third (Ex.102c) shows the C-type with sequence-contraction, and in this draft the final motive has been found, in addition to the rhythm.

The final form (Ex.102d) is a varied S 16.

We had another instance of this transformation of the C- to the S-type in Ex.4 from the trio in the eighth symphony (see p.7). This practically exhausts the list of cases forming the group of changes in form that lead to an S-type. Moreover, it is obvious that the theme with the liaisons characteristic of the C-type cannot straightway be turned into the S-type. For the liaisons in the latter are more fixed and wider in their embrace than in the former; and in the S-type the antecedent and consequent are more closely connected in their first segments.

The reverse change-of the S-type into the C-type is therefore more common, especially as the liaisons in the consequent are easily modified by means of sequences.

|

The theme of the minuet in Op.18. V

(Ex.37) was

of a varied S-type in the sketch; but in the final form it

is a C 12 with the structure:

4 (anteced.) + 2 x 2 (contin.) + 4 (conseq.)

The theme of the presto in the seventh Symphony already referred to (Ex.97) also shows this development.

|

|

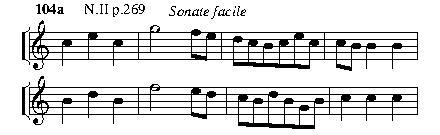

|

in a later sketch (Ex.104b) the theme is changed, without characteristic liaisons being introduced.

Finally (Ex.104c) an S8 appears, in which the continuation is added to the antecedent in the form of a sequence.

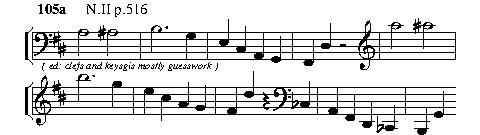

I shall now refer to some instructive instances in which the sketch belongs to the C-type. When we were considering the up-beat, I mentioned the eight-bar theme of Op.132, together with the sketches leading up to it (Ex.19).

|

|

|

|

|

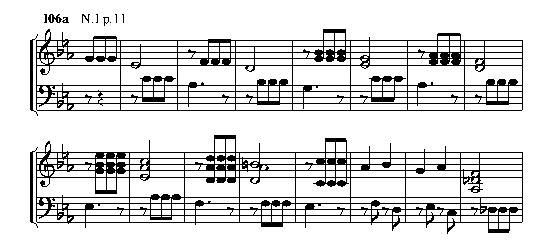

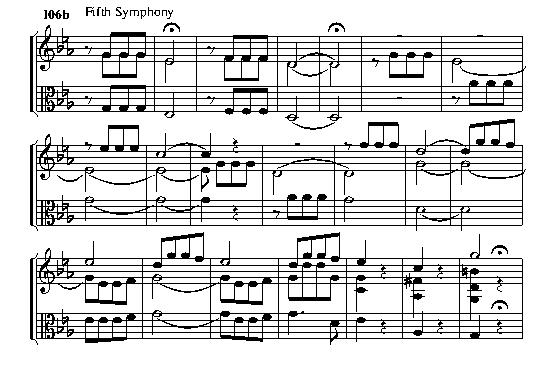

5 (curtain) + 2x4 (anteced.) + 3x2 (contin.) + 2 (conclus.) = 5 + C16

Schmitz (p.79) says of this passage, 'We might also imagine it scored as follows: (Ex.107) It is easy to imagine the guiding melodic line as played by the first violins alone, the sustained notes being held by the second violins, violas, and cellos. The imitations . . . as they appear in the actual score, do nothing to alter the rhythmic symmetry of the structure,'

But I consider that the regular one-bar rhythm would become too insistent, and would drown the effect of the four-bar sequences. The way in which the form is developed shows that the instrumentation is essential, and determines the structure here; it is not a secondary consideration as Schmitz suggests.

|

|

The final form retains the sequence and consists of eight bars. The retention of the first dotted minim throughout all the sketches shows that it was an essential part of the melody; the last note acts both as end and as beginning. Here again, we see the C-type expanded to eight bars.

I have repeatedly pointed out that in Beethoven's works the C-type is either 8 or 16 bars in length: and so, as regards the number of bars, it is broadly comparable with the S-type. The latter must of necessity have this number of bars, but the former is not limited in that way. The liaisons characteristic of it are quite different, and Fischer has thoroughly demonstrated the basis on which they rest. Riemann is certainly wrong in thinking that all themes have the S-type as their foundation. This explains, however, why his method of analysis so often does violence to the themes he is considering.

This connection that exists in Beethoven's music between the two essentially different types explains the important part played in his compositions by the mixed forms, S(C) and C(S), to which I have already referred. Both forms fall in readily with the four-bar structure. They are far wider in their embrace than are the simple S- and C-types. And it is one of the peculiar features of Beethoven's style that each part of a phrase shall encompass more than do those that precede it.

Let us first consider simple cases where, in an S-type,

the antecedent or the consequent is, or both of them are,

of the C-type; the result is a mixed type, S(C). We

saw an instance of this in the finale theme of Op.18. VI

(Ex.87)

where both antecedent and consequent are C8.

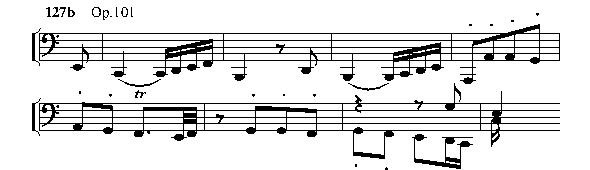

In Ex.99 (Ex.99) likewise we get the development of the

adagio theme in Op.101 to a 16-bar S(C) of the form 8+8.

In the theme of the rondo of Sonata Op.24

(Ex.98)

the subsequent is lengthened so that the S(C) type has 8+10 = 18 bars.

|

|

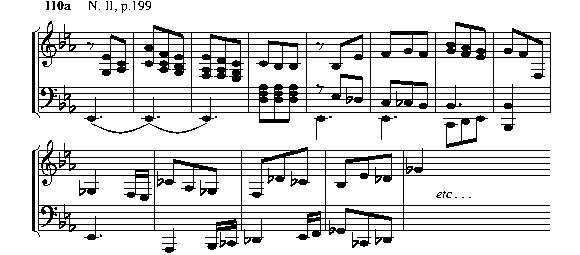

|

From this, by retention of the first four bars and elaboration of the bass motive in bars 10-11, the final form (Ex.110b) developed a C8. With a four-bar antecedent and continuation; repetition with modified cadence made this into a sixteen-bar S (C). The postlude is not part of the theme: for the repetition,while varying the theme, fundamentally alters the consequent.

|

|

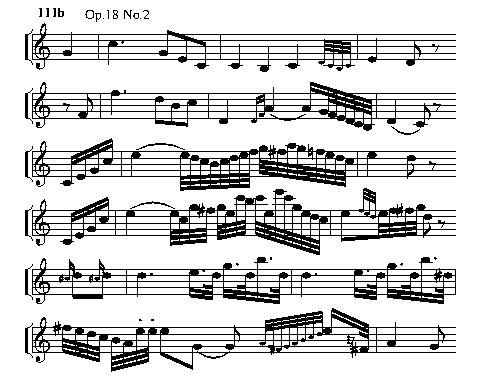

1+2+1+2 (anteced.=S6) + ||:2:|| + ||:1:|| (contin.) + 2 (conclus.) = C14

Even if we choose to reckon as part of the theme the twelve bars that follow, up to the intervening allegro, this would only mean that the conclusion had also become a C.

|

|

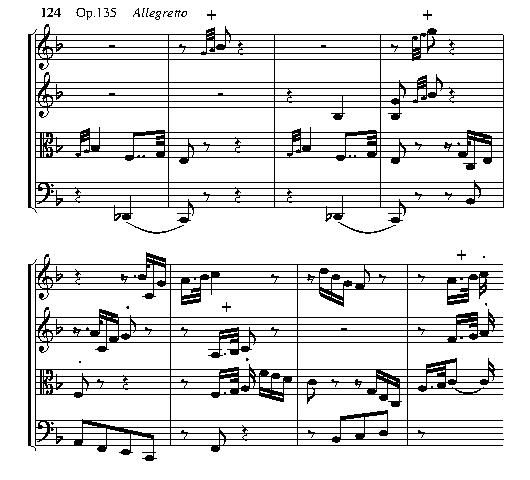

In this case also the first four bars are retained and expanded to eight by repetition (ex.112b) . These eight bars are repeated with so much alteration in the instrumentation and the accompaniment, and with such different cadences, that we may speak here of an S16 as antecedent; then follows the 8-bar continuation with contraction. The sketch shows conclusively that these bars belong to the theme.

|

|

|

|

The next sketch (Ex.113b) substitutes for this a definite S8 followed by a continuation.

These liaisons are still more schematically shown in a later experiment (Ex.113c), where the complete echoes are introduced only after the main sections.

In the final form (Ex.113d) the echoes are shortened but occur more frequently; they are no longer mere interpolations, but aid in the production of form. They constitute a kind of sequence, and so help out to the liaisons: for it is not easy to decide whether the final theme belongs to the S- or to the C-type. As a matter of fact, the two types are completely interwoven in the sketches. Here we are dealing with a theme that is characteristic of Beethoven's mature style; in a later section (Chap. II(g)) I shall attempt to explain the peculiarities that such themes illustrate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

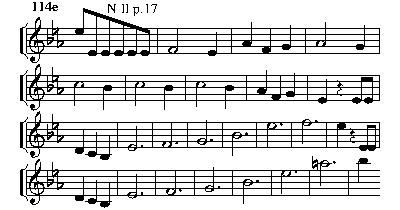

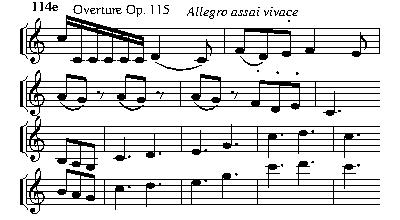

It still keeps this number of bars in Ex.114b, but now contains sequences, the elements of the C-type.

The object of the two following experiments (Ex.114c and d) was to arrive at a different number of bars by means of sequences.

Ex.114e gives the result; the theme now runs to nine bars. What is unusual, however, is that an S 16 follows this C9, and is actually in melodic contrast to it. In Beethoven's work this occurs seldom (Gal p.68) and it is quite contradictory of Schmitz's principle of 'contrasting derivation'.

Finally (Ex.114f), the double bars are combined as simple 6/8 time. The irregularity is retained; the antecedent in the C-type has an apparent length of 5 bars, but as a matter of fact the number of bars is even, for the first is an up-beat or curtain; the high note always lies in the second part of the bar, as is shown by sf frequently being written above it in the overture; 114e is very different in this respect. Half-bars would therefore give the correct number of bars and the stress in the antecedent; in the consequent the reverse occurs.

All this may explain why this overture is not accounted one of Beethoven's best works. The process of getting it into shape cost him a great deal of labour, and even in the end he did not achieve a perfect result. The substitution of the S-type for the continuation is not really suitable.

Ex.91 from Op.1 No.3 gave a case in which the antecedent in a C(S) is an S, and this method of building up the theme gives essentially better results.

What we learn from these and similar examples be summarised as follows:

Before going on to investigate a final characteristic displayed in Beethoven's themes, let me say a word concerning certain themes with an irregular number of bars. It would appear that in many cases special features conceal or counter-balance these irregularities; such examples accordingly serve to strengthen statement 2 above.

We can also see the derivation from the sketches.

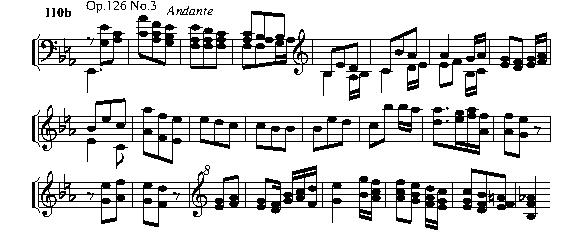

In Ex.111 we had a theme from

Op.18 No.2, of the C(S) type and of 14 bars. The

antecedent of the song has six bars; the sketch shows

the development from four regular ones; the irregularity

is scarcely perceptible. The minuet from the

trio Op 1 No.3 (Ex.91) has as antecedent an S-type

of seven bars; it is completed by the addition of a rest

to the last bar and of five bars to the continuation that follows.

The effect of the whole is to make the

irregularity of the several parts less obvious. The original

nal sketch had eight bars, and the same is true of the

Scherzo theme in Op.106; whereas in the final form the

number of bars is seven. I have already explained why the one bar was taken out

(Ex.24 and p.67).

The first theme of the quartet Op.18 No.5

(Ex.54)

is also only apparently eleven bars long; the sketch had the structure

4 (curtain) +2+2+2+2 (S8).

I have explained that Beethoven

replaced the note-repetition by a swinging movement,

and this involved shortening the curtain by a bar; the

actual theme is an S8. The adagio of the ninth symphony

(Ex.113)

is full of repetitions, which involve a new irregularity

in the number of bars, an irregularity

that does not appear in many of the sketches. I have

already drawn attention to the important part these

echoes play in form-production; but they have another

purpose, and the consideration of this leads me on to yet

another feature in Beethoven's style.

Wetzel in an account of Kurth's work 'Romantic harmony' says: 'Bach and Beethoven took great pains to achieve an increasingly perfect rhythmical organisation of the succession of sounds in their works. Kurth fails to recognize its development to subtlety from a very obvious foundation. He fails to realise . . . that Bach and Beethoven in their mature years composed melodies without definite limit, which overflowed the strophic limits, and that they were not in the least ashamed of these.' Throughout this chapter we have striven to follow 'these subtle developments to a perfect rhythmical structure' in the case of Beethoven, and, in so doing, to reveal the course he pursued and the laws that were established; for the liaisons characteristic of the several types of melody are nothing more or less than a rhythmical organization of this kind. Comparison of the sketches and the finished works would also have brought us to the conclusion expressed in Wetzel's second statement.

I have already analysed the remodelling undergone by the theme of the allegro appassionato in Op.132 (Exs. 6 and 73). The liaisons characteristic of the melodic types form sections separated by caesurae. Normally, the eight-bar S-type has one main caesura between the fourth and fifth bars; and between the second and third or sixth and seventh there are subsidiary caesurae. In the C-type all are distributed in accordance with its structure; sequences naturally tend to involve caesurae of this kind. Now let us consider the effect of such a theme in its final form. The literature on Beethoven is unanimous in its opinion. Helm (p.290) calls it 'one of the most impressive that he ever discovered'; Thayer (V p.269) writes: 'The melody of the movement is certainly one of the most beautiful that Beethoven ever wrote'.

|

|

|

|

|

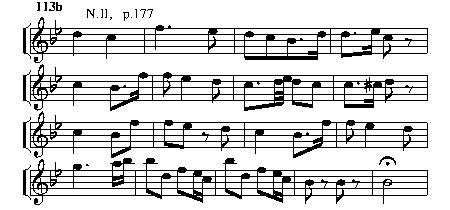

Again in the final form (Ex.115b) we find these caesurae bridged by repeated notes and syncopated slurs. At the same time, the subsequent is so markedly altered that it loses its liaisons with the antecedent, and a C8 is produced.

I have already drawn attention to the filling-in of the rest in bar 2 of the slow movement in Sonata Op.90 (Ex.1 and p.5). Now we see that the reason for this was to get rid of the caesura in that bar. Concerning this particular instance Nottebohm remarks (N. II, p.366) that by the alteration of one note 'the melody is given a significance that it originally lacked'. The change is effected, however, not by this one note alone, but by the repeated note which bridges the caesura.

The theme for variations in Sonata Op.109 (Ex.26) illustrates the same thing. The sketch still shows clearly the main caesura between bars 4 and 5; in the final form this is bridged by a repeated note and an appoggiatura chord. The way in which this chord is written is not mere chance: it imposes a dynamic connection with the preceding part of the bar, and - let me once more emphasize this point - it puts the melodic apex in an effective position.

|

|

2+2 (anteced) + 2x1 + 2x½ + 1 (contin) = C8.

The caesurae in bars 2, 4, 5, and 6 are very conspicuous.

In the final form (Ex.116b), this is changed. Here the liaisons are weakened, the caesura in bar 4 is got rid of by repetition of a note over the same accompaniment, and that in bar 2 by removal of the rest.

|

|

In the fourth bar of the adagio in Op.59 No.1 the harmonized suspensions (Exs. 52 and 78), by means of the tension they produce, bridge to some extent the marked caesurae in the sketch.

|

|

|

|

The foregoing examples and the explanation that I have given of them justify the following conclusions:

|

|

|

|

|

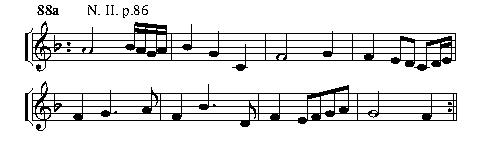

As further examples may be mentioned the theme of the first allegro in Op.74; the minuet from Op.59. No.3 (Ex.88), which in spite of being constructed on the S-type shows scarcely any caesurae; the third movement of Op.18 No.3; and the slow movement of Op. 18. No.1, with its accompaniment in triplets. I have purposely chosen early examples: in these Beethoven does not so completely avoid caesurae as he does in the later works already mentioned.

|

|

|

|

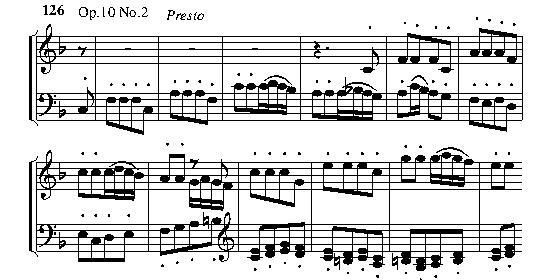

In considering these movements we see something

new, which, however, is on the same lines as the fact

of a regular number of bars in the C-type melodies,

already referred to. The length of the fugue theme is

such that a phrase of 8, 16, or 12 bars results. We can

think of the theme from Op.2 No.3

(Ex.125) as evolved

from a threefold repetition on the plan

3x2 + 2 = 8;

similarly, the presto theme (Op.126) has the structure

3x1 + 1 = 4 in triplicate. The fugue and fugato

themes of the later period also show the same regularity

in the number of bars. That from Op.131

(Ex.10)

is in four bars, and is repeated four times in succession.

|

|

The theme of the fugue in Sonata Op.110 is in four bars,

with the structure 3x1 + 1;

an irregularity comes in with the entry of the third part,

since the second part lengthens the theme by two bars.

The theme of the second movement in the ninth symphony

is also in four bars, and it is easy to find other examples

in the Missa solemnis and the fugue for string quartet Op.133.

Of course, we find instances of different structure, such as the irregularity in the entry of the parts in Op.110, to which I have just referred. But in comparison with the variety in bar-number and number of entries of the fugue themes of Bach's 'Well-tempered Chavichord' we are justified in making some such statement as the following. In Beethoven the theme of the fugue or fugato, and also the passage that involves the entry of the several parts (exposition) usually display the same regular number of bars as do themes of the S- and C-types.

This concludes what I have to say regarding the study of thematic form yielded by a comparison of the sketch with the completed work. Our investigation has shown that in many cases where the motive is retained a great portion of the work is expended on the production of form; our study has yielded us the types and the laws governing these forms, and we have learnt more about them than has been known hitherto.

Our study, however, has been based on the works of Beethoven alone; so that for the time being the points we have discovered concerning style must hold good for him alone. We must reserve for a more extensive study the detailed demonstration of the differences between, say, the classical composers of the Viennese school; in the foregoing I have hinted here and there at the lines that this investigation should follow. I believe that, especially as concerns the C-type, it will be found that similar differences occur in the number of bars used for the theme and in the formation of mixed types, as I have already shown they do in the case of the melody based on triplication (p.46 et seq.). I find support for my view in Essner's observation that 'continuation-types in eight bars are rare among the works of Haydn'.

Continued from Part I: The melodic line

See also:

Index of Opus-numbers,

List of Abbreviations,

Bibliography,

Editor's notes

Also:

www.pjb.com.au,

www.pjb.com.au/mus